Beaver Valley Expressway

James E. Ross Highway

Penn-Lincoln Parkway

Beaver Valley Expressway

James E. Ross Highway

Penn-Lincoln Parkway

Back in the late 1940s, as the steel industry was heating up in Pittsburgh, it was determined that something had to be done for transportation into and out of the city. Called to help with the planning of the "new Pittsburgh" was Robert Moses, known for helping to shape New York City's highway transportation network, devised a plan that included the Crosstown Boulevard as well as the Penn-Lincoln Parkway.

The Penn-Lincoln Parkway actually was first envisioned in the Model-T days of 1921, when the Citizens Committee on City Plan of Pittsburgh the forerunner of the Regional Planning Commission, set forth a plan to upgrade Second Avenue into a four and six-lane boulevard and extending it through Nine Mile Run to Swissvale. In April 1924, the Boulevard of the Allies Extension Association was formed by residents of the East End to promote extending the boulevard through Squirrel Hill, Swissvale, Rankin, and Braddock to East McKeesport. Later that same year, the Allegheny County Department of Public Works considered the idea and made some preliminary studies.

In 1930, Pittsburgh Department of Public works became interested and began to collaborate between City and County engineers. Between 1930 and 1933, the County was actively pursuing the extension and spent close to $7,500 on surveys and plans. The route would be via Forward Avenue and bypassing Wilkinsburg but not traveling south through Braddock. On the other hand, the City Planning Commission began studying an extension of the boulevard in 1930 as well. However, their report in 1933 set forth a route with a proposed tunnel under Schenley Park.

In 1934, a group of prominent citizens from the East End created the Penn-Lincoln Highway Association to promote a highway improvement. An engineering committee which included representatives from the Department of Highways District 11-0, City and County Planning Commissions, and the City and County Departments of Public Works was created. Its task was to recommend a location for the part of the highway east of downtown, which until that time had different routes proposed. In 1935, the County Planning Commission proposed an eastward highway almost identical in alignment to today's Parkway, with the exception of double-decking parts of Second Avenue which was rejected.

On April 9, 1937, a caravan of state officials as well as representatives of the Pittsburgh and Allegheny County governments and Penn-Lincoln Highway Association drove from Churchill to Campbells Run Road. After encountering the perils faced by trying to traverse the urban landscape with traffic signals, stop signs, and congestion, state officials agreed to adopt the Penn-Lincoln Highway as a state project at a dinner that evening.

Later in 1937, the Department of Highways' district engineer began studies and compile estimates on the Parkway. The County planning engineer was authorized to cooperate and provide assistance such as engineering services.

The US Bureau of Public Roads announced its approval of the expressway plan on September 16, 1938. The approved routes were virtually identical with the present Parkways, right down to the Squirrel Hill and Fort Pitt Tunnels. It would not be until 1941 when the Federal Public Roads Administration formally agreed to match state funds and prepare for construction.

As World War II was drawing to a close in 1943, postwar planning began in earnest in Pittsburgh. The Allegheny Conference on Community Development was formed as a private citizens' organization to spearhead improvement programs such as the Penn-Lincoln Parkway. When the war concluded in 1945, the parkway was ready to begin. Through the influence of Attorney General James H. Duff and Richard K. Mellon, Governor Edward Maring approved $57 million for improvements in Pittsburgh, of which two were the Parkway, Crosstown Boulevard, and Point State Park construction. The plan was devised by Robert Moses, who was known for planning New York City's highway transportation system.

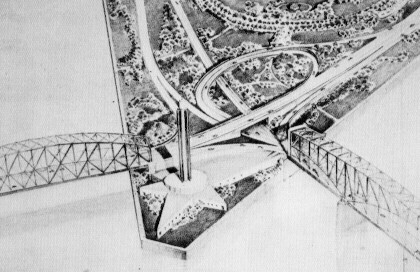

Moses' planned Point Interchange utilizing the

former Point

and Manchester Bridges. Instead of the

fountain, a beacon

was to be the center of focus at the point. I think the fountain

was a good choice. (Arterial Plan for Pittsburgh)

Chief Engineer of Road and Chief Engineer of Planning for Allegheny County, and eventually Secretary of Highways during I-376's construction, E. L. Schmidt sought through the years to convert his vision into reality and received help from several administrations. Governor Edward Martin (1943-1947) approved legislation establishing the expressway and in his term, work would begin from US 22 to US 30. Governor James Duff (1947-1951) made the Edgewood interchange, Commercial Street viaduct, roadway from Bates Street to Frazier Avenue bridge, Squirrel Hill Tunnel, and to Forward Avenue possible. Governor John Fine (1951-1955) continued construction on the Squirrel Hill Tunnel and interchange with Bates Street, bringing the Parkway to completion.

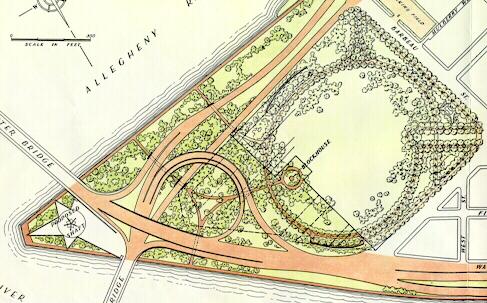

Detailed drawing of the interchange at the Point. (Arterial Plan for Pittsburgh) |

|

|

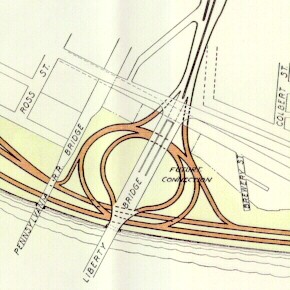

Drawing of the proposed interchange between the Pitt Parkway and Crosstown Boulevard. (Arterial Plan for Pittsburgh) |

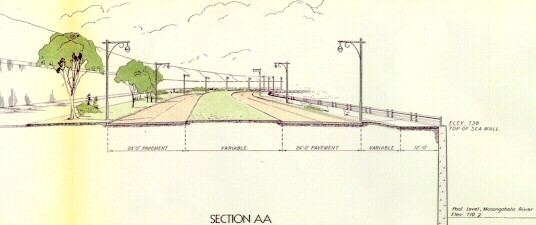

Cross section of what the Pitt Parkway would have looked like. (Arterial Plan for Pittsburgh) |

Cross

sections of the Pitt Parkway ![]() - Arterial Plan for Pittsburgh

- Arterial Plan for Pittsburgh

The Department of Highways proposed a parkway from US 22 in Churchill to downtown and out to the new Greater Pittsburgh International Airport in May 1944, to be called the Pitt Parkway after Moses' suggestion. However, unlike his plan, the Parkway would not have at-grade intersections at certain areas, and the name changed to reflect the confluence of the two highways that would be carried: William Penn and Lincoln. Most of alignment that was proposed was used in the final design and construction; however, the one section that was under debate was from the Edgewood-Swissvale area to downtown. The three routes that were studied were the Penn Avenue Alternate, Fifth Avenue Alternate, and the adopted location. The specifics of the routes were as follow:

Squirrel Hill

Tunnel Specifications ![]() - Pennsylvania Department of Highways

- Pennsylvania Department of Highways

Ground was broken on July 25, 1946 when Alexander Alden of West Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania climbed aboard a Caterpillar D-8 and commenced bulldozing from Greensburg Pike to Ardmore Boulevard in Wilkinsburg. The sound of timber crashing to the ground signaled the start of a transportation revolution in the Steel City. Johnson, Drake, and Piper, Inc. of New York was the general contractor, having submitted a low bid of $2,042,368. The excavation and grading working was completed by the M & S Construction Company, Inc. of Pittsburgh.

One of the more challenging aspects of the project was what to do with Squirrel Hill which sat in the path of the expressway. Excavating a cut would destroy an extensive residential area including a large apartment complex, a church, and a school, so a tunnel was proposed as the solution. The expressway would enter from the east via a deep ravine where Nine Mile Run flows through. Traffic surveys showed that volumes would reach 40,000 vehicles per day by 1960; therefore, twin tubes each carrying two 12-foot lanes were approved. Ole Singstad, an internationally recognized name in tunnel design, was retained for the project.

The tunnel project experienced a delay in March 1948, due to the lowest bid placed at that time at $18 million, an offer that was promptly turned down by the state. That bid called for complete construction, but the Department of Highways saw no need to include items like the lining and roadway surface while material costs were high following World War II.

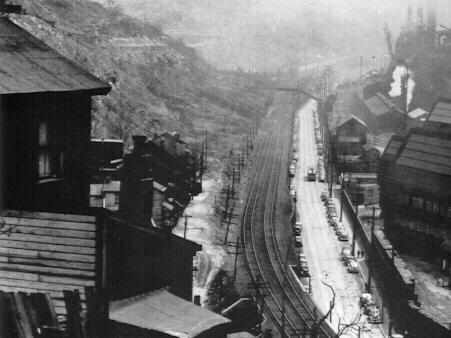

View along Second Avenue in 1948. The hillside is currently

where I-376 runs. (Todd Webb)

On August 5, 1948, the Department of Highways announced that construction of the 4,200-foot-long Squirrel Hill Tunnel would begin by September 1. This would become the department's largest contract ever awarded to that time, totaling $13,767,843 went to B. Perini & Sons, Inc. of Framingham, Massachusetts. This did not include construction of the tunnel lining and highway surface inside the tunnel, nor the ventilating building or pavement of the approaches. Excavation would commence on November 21, 1948 with drilling progressing on both tunnels at 12 to 24 feet per day. Breakthrough ceremonies took place on September 15, 1949 when workers from both sides of Squirrel Hill met in the middle of the future tunnel.

Workers used many unique items in the construction of the tunnel. A large metal turntable to allow trucks to enter the bore and turn around after being filled with material. Huge steel forms on rails were used for creating the lining by forcing the concrete to encase the rocks and earth in a solid wall.

Before the roadway opened to traffic, one Pittsburgher took an unfortunate trip, or I should say fall, on the Parkway. Eight-year-old Jack Kravetz of Squirrel Hill, was playing on an overpass still under construction just west of the Squirrel Hill Tunnel. Children's Hospital reported that he had suffered a fractured skull, fractures of the right and left arms and left leg, possible internal injuries, a bruised eye, and other body contusions. Pittsburgh Police determined that he had not been hit by a car, but rather lost his balance and fell. His body was found underneath the Beechwood Boulevard ramp by a man whose car had run out of gas and he happened to be walking to a telephone.

Governor John S. Fine cut the ribbon to open first section from Exit 72B to Exit 80 on June 5, 1953, which included the tunnel. This was the first modern expressway to be built in Pittsburgh. It was also a tricky project, that not only involved mining coal vein under the Ardmore Boulevard interchange but also practically blasting into the basements of some buildings on the Squirrel Hill Tunnel section. About 400,000 cubic feet of earth was moved in its construction. Unfortunately, construction of the tunnel cost the lives of three workers out of a total of six who died in construction of the entire section.

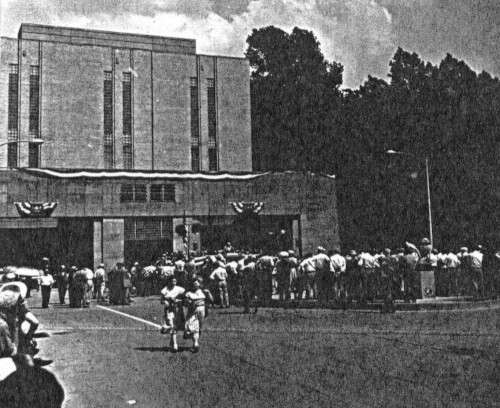

Opening ceremonies for the Squirrel Hill Tunnel on June 5, 1953.

(Clyde Hare)

The tunnels are 4,225 feet-long, 29 feet, 1 3/4 inches wide, and a vertical clearance of 14 feet from pavement to ceiling. The arched roof above the ceiling has a radius of 19 feet and 3 inches. The tubes are 27 feet apart. There are eight passage ways located at 500 feet intervals between both tunnels, with an emergency phone and steel doors to protect people using them from fire and air currents. A complex system of drainage, telephone, electric, water, fire alarm, ventilating lines, as well as pipes for drawing air samples into analyzers are located underneath, above, and behind the walls of the tunnels. Fire alarm boxes are placed at frequent intervals and tow trucks equipped with fire fighting apparatus and other emergency equipment are permanently stationed at the tunnels. Outside the tunnels were photo-electric tubes that scanned each vehicle to see if it would clear the tunnel. If a vehicle cuts the beam produced by these tubes, signals will turn on to halt the vehicle and warn motorists within or approaching the tunnel. They were so sensitive that it could detect an object less than one inch in size moving at 60 MPH. Bells will ring to alert workers at the tunnel to take the vehicle off the Parkway. If a fire breaks out, a similar system goes into action that alerts workers in the control room with a bell and red light. In addition, 84 fire extinguishers are installed.

Air is continually analyzed, and if a concentration of fumes is detected, warning lights will go off in the control room. The sampling tubes are located throughout the tunnel to detect high concentrations of carbon monoxide or other fumes, and if high enough, crews are alerted. Four fans are located in the ventilation buildings on either end of the tunnel and the air forced through air ports of various sizes and spacing to maintain a consistent healthy air flow. Two-way dampers make it possible to exhaust or blow air into the tunnels. Air will not only be controlled on the basis of traffic density, but also the direction of outside air and barometric pressure.

Westbound heading towards Bates Street in August 1953.

(Harold

Corsini)

The original ceiling of the tunnel were suspended by stainless steel hangars from the arch of the tunnel bore that is now visible after removal of the suspended ceiling took place in 2012. A drainage system underneath the tunnel keep the lanes dry. Water lines are included for fire fighting and maintenance. Fire clay brick was used on the floor as a wearing surface with a center line of white brick to separate travel lanes. They sat on 10-inch thick concrete which itself is laid on 12-inch thick coarse aggregate. The tubes have two continuous rows of florescent lights with white tile walls and white painted ceiling. Enamel-coated walk railings were used to accentuate the illuminations, but were removed in the rehabilitation in the 1980s. High powered lighting was used at the entrances so that drivers could get accustomed to the artificial lighting. Someone traveling at 40 MPH could get used to the interior lights within 30 seconds.

| Quantities of Materials | |

| Excavation | 3,897,000 cubic yards |

| Concrete for Structures | 209,000 cubic yards |

| Concrete Pavement | 326,000 square yards |

| Reinforcement Bars | 15,165,000 pounds |

| Fabricated Structural Steel | 33,245,000 pounds |

| Wire Mesh Reinforcement | 3,100,000 pounds |

| Penn-Lincoln Parkway Designs from 1952 | |

| Picture | Source |

| Proposed Parkway West in Carnegie | Paul Slantis |

| Proposed Parkway West in Greentree | |

| Proposed Parkway West and New Tunnel | |

Construction began on July 25, 1950 when Governor James Duff tossed the first spade of dirt. On October 15, 1953, Governor John Fine and other dignitaries joined together on a platform at the Carnegie interchange to open the first section of expressway between Saw Mill Run Boulevard and its western terminus near the airport. Authorities said the 15-minute drive between downtown and the airport would be the "shortest trip to a major air terminal" in any city in the country. Traffic utilized the West End Bypass to detour around the unfinished tunnel and bridge. On July 11, 1954 contracts for the initial design of the tunnels were awarded. The groundbreaking for the tunnel was held on April 17, 1957 with the drilling commencing on August 28, 1957. The price tag for the project would be $17 million. On March 31, 1958, Mayor David L. Lawrence and Governor George L. Leader pushed the button that triggered the blast to eliminate the last amount of rock between the two tunnel bores from the opening in the side of Mount Washington facing downtown Pittsburgh. The Fort Pitt Bridge opened at 11 AM on June 19, 1959, which connected downtown to West Carson Street and replaced the old Point Bridge. At the time, it was the only double-decked, tied-arch bridge. The bridge became the center of attention three years later when a man climbed to the top of the arch on the upriver side and threatened to jump. In one of the first instances of television capturing a breaking story live, a KDKA-TV cameraman followed the man to the top to talk him down. Unfortunately, he was not successful as the man jumped into the Monongahela.

The $16 million Fort Pitt Tunnels opened at 2 PM on September 1, 1960, completing the Penn-Lincoln Parkway from Monroeville to the Airport. Originally conceived as a toll facility, Governor David Lawrence remarked at the opening: "As you know, this tunnel was originally intended as a toll facility. The fact that it is being opened, today, as a toll-free tunnel is one of the better pieces of news we have had for this community." The tunnels are 3,600 feet in length with 14 feet of clearance. Each portal has four centrifugal fans that push air through the tunnels and remove car exhaust.

Specs

for the Fort Pitt Bridge ![]() - Pennsylvania Department of Highways

- Pennsylvania Department of Highways

Specs for the

Fort Pitt Tunnel ![]() - Pennsylvania Department of Highways

- Pennsylvania Department of Highways

| Penn-Lincoln Parkway Construction | |

| Picture | Source |

| Fort Pitt Bridge in 1958 | Paul Slantis |

| Northern Portal of the Fort Pitt Tunnel | |

| Southern Portal of the Fort Pitt Tunnel | Pennsylvania Department of Highways |

| Above Carnegie Facing West in 1951 | Clyde Hare |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Construction costs came in at $14,630,000 with the Saw Mill Run Boulevard interchange making up $4,083,000 of that total. The Carson Street interchange cost $1,500,000, Fort Pitt Bridge cost $6,305,000, and downtown approaches to the bridge at $8,800,000. The total cost of the western half was $31,235,000.

Did you know that the double-rail barriers formerly on the Fort Pitt Bridge were actually installed backwards? You can still see an example of the backwards barrier on the Fort Duquesne Bridge, the Boulevard of the Allies, and the ramps around Point State Park. In 1962, a report was issued to have the railings installed with them facing inward to the highway which explains why I-579's look they way they do. This means that fewer truck accidents and payloads landing in Point State Park could have happened if the then Department of Highways would have re-bolted the brackets in response to the report.

Construction began on July 25, 1950 when Governor James Duff tossed the first spade of dirt. On October 15, 1953, the first section of expressway opened from Saw Mill Run Boulevard to its western terminus near the airport with traffic using the West End Bypass to detour around the unfinished tunnel and bridge. On July 11, 1954 contracts for the initial design of the tunnels were awarded. The groundbreaking for the tunnel was held on April 17, 1957 with the drilling commencing on August 28, 1957. The price tag for the project would be $17 million. On March 31, 1958, Mayor David L. Lawrence and Governor George L. Leader pushed the button that triggered the blast to eliminate the last amount of rock between the two tunnel bores from the opening in the side of Mount Washington facing downtown Pittsburgh. The Fort Pitt Bridge opened at 11 AM on June 19, 1959, which connected downtown to West Carson Street and replaced the old Point Bridge. At the time, it was the only double-decked, tied-arch bridge. The bridge became the center of attention three years later when a man climbed to the top of the arch on the upriver side and threatened to jump. In one of the first instances of television capturing a breaking story live, a KDKA-TV cameraman followed the man to the top to talk him down. Unfortunately, he was not successful as the man jumped into the Monongahela River.

The next section to open was from Bates Street to the Boulevard of the Allies at 11 AM on September 10, 1956. However, only the eastbound lanes opened to traffic and so drivers had to wait another 19 days until the opening of the westbound lanes.

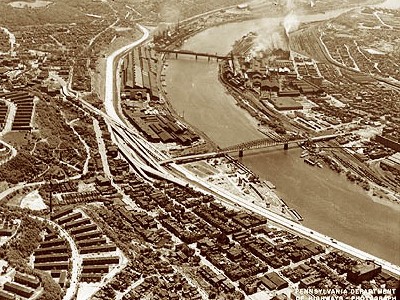

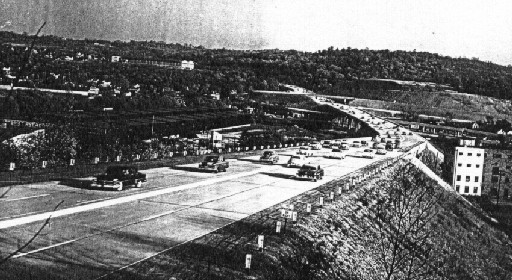

View of the Parkway at the Boulevard of the Allies

interchange in 1958.

(Pennsylvania Department of Highways)

A milestone was reached on January 17, 1958, when the first downtown link of the Parkway East opened. The eastbound ramp from Grant Street and the expressway to the Forbes Avenue interchange saw its first vehicles that day. Other Downtown ramps leading to the eastbound parkway opened in July and August 1958. By September of that year, traffic entering at the Point, or from Market, Wood, or Grant Street had an unimpeded ribbon of highway to travel to the eastern suburbs.

The last section to open was from the Point to Exit 2B in 1959. The reason for the delay was that it was necessary to move the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad buildings and track near the Grant Street interchange. Also, weaving the highway in between the elevated eastbound lanes of Fort Pitt Boulevard took time.

A total of $31,235,000 was spent on the Parkway East. The expressway from Churchill to the Boulevard of the Allies interchange cost $16,541,000 in addition to $18,111,000 for the Squirrel Hill Tunnel and from that point to the Fort Pitt Bridge came in at $25,220,000. The Boulevard of the Allies interchange cost $4,700,000 itself with the ramps and underpasses west from Tenth Street cost $10,200,000. The relocation of Second Avenue cost $4,300,000. Construction costs came in at $14,630,000 with the Saw Mill Run Boulevard interchange making up $4,083,000 of that total for the Parkway West. The Carson Street interchange cost $1,500,000, Fort Pitt Bridge cost $6,305,000, and downtown approaches to the bridge at $8,800,000. The total cost of the western half was $31,235,000.

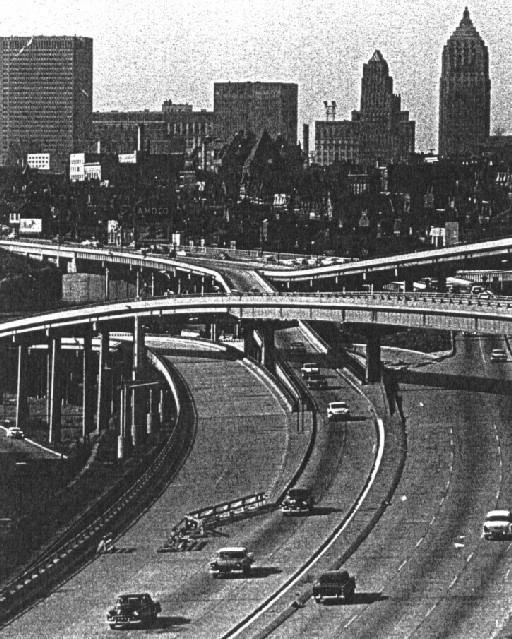

Temporary end of the Penn-Lincoln Parkway at the Boulevard of the Allies

in 1959. (Clyde Hare)

The Penn-Lincoln Parkway in Carnegie in

1953 facing towards downtown.

(Don Bindyke)

| Penn-Lincoln Parkway West Designs from 1952 | |

| Picture | Source |

| Proposed Parkway West in Carnegie | Paul Slantis |

| Proposed Parkway West in Greentree | |

| Proposed Parkway West and New Tunnel | |

Construction began on the Parkway West on July 25, 1950 when Governor James Duff tossed the first spade of dirt. On October 15, 1953, Governor John Fine and other dignitaries joined together on a platform at the Carnegie interchange to open the first section of expressway between Saw Mill Run Boulevard and its western terminus near the airport. Authorities said the 15-minute drive between downtown and the airport would be the "shortest trip to a major air terminal" in any city in the country. Traffic utilized the West End Bypass to detour around the unfinished tunnel and bridge.

| Penn-Lincoln Parkway Construction | |

| Picture | Source |

| Fort Pitt Bridge in 1958 | Paul Slantis |

| Northern Portal of the Fort Pitt Tunnel | |

| Southern Portal of the Fort Pitt Tunnel | Pennsylvania Department of Highways |

| Above Carnegie Facing West in 1951 | Clyde Hare |

Construction on the Fort Pitt Bridge began in 1954; however, work on the superstructure was delayed for three years. The reason being was a disagreement between city and state officials over whether the span should accommodate trolley lines. The Pittsburgh Railways Company argued that their West End trolley system would be destroyed without tracks on the new bridge and if the Point Bridge, which had trolley tracks, was torn down. Local and state planners argued that permitting trolley lines would negate their aim of a high-speed highway through Pittsburgh. The Pennsylvania Public Utilities Commission eventually ruled in the favor of the planners and the tracks were eliminated from the bridge designs. The ruling was challenged in court, and it wasn't until January 1956 that the Pennsylvania State Superior Court upheld the PUC decision.

After five years, it opened at 11 AM on June 19, 1959 amid fanfare and cheers, replacing the old Point Bridge which would stand for another decade before being demolished. As a ceremony at the foot of the bridge in Gateway Center, Governor David L. Lawrence, who was one of the driving forces behind the bridge and tunnel project, referred to the opening as "a high spot in Pittsburgh's observance of it's 200th birthday." Following his remarks, the Governor along with other officials, cut the ribbon signaling its opening. The Governor, Mayor Thomas Gallagher, and other dignitaries climbed into a Cadillac and joined a 13-car caravan led by State Senator Joseph Barr for the inaugural trip across the span.

At the time, it was the first double-decked, tied-arch bridge in the world and first to be designed entirely by computer. The bridge became the center of attention three years later when a man climbed to the top of the arch on the upriver side and threatened to jump. In one of the first instances of television capturing a breaking story live, a KDKA-TV cameraman followed the man to the top to talk him down. Unfortunately, he was not successful as the man jumped into the Monongahela.

Fort Pitt

Bridge Specifications ![]() - Pennsylvania Department of Highways

- Pennsylvania Department of Highways

On July 11, 1954 contracts for the initial design of the tunnels were awarded. The ground breaking for the tunnel was held on April 17, 1957 with the drilling commencing on August 28 of that year. The price tag for the project would be $17 million. On March 31, 1958, Mayor David L. Lawrence and Governor George L. Leader pushed the button that triggered the blast to eliminate the last amount of rock between the two tunnel bores from the opening in the side of Mount Washington facing downtown Pittsburgh.

The $16 million Fort Pitt Tunnels opened at 2 PM on September 1, 1960, completing the Penn-Lincoln Parkway from Monroeville to the Airport. Originally conceived as a toll facility, Governor David Lawrence remarked at the opening: "As you know, this tunnel was originally intended as a toll facility. The fact that it is being opened, today, as a toll-free tunnel is one of the better pieces of news we have had for this community." If it had been built as a toll bridge/tunnel, it would have been the only tolled tunnel in Pennsylvania outside of the ones on the Turnpike. The toll plaza would have been located on the western side of the tunnel complete with 10 booths. For frequent travelers, the state would have issued monthly stickers such as what the Connecticut Turnpike did for commuters there.

The tunnels are 3,600 feet in length with 14 feet of clearance. Each portal has four centrifugal fans that push air through the tunnels and remove car exhaust. It was also the first vehicular tunnel in the world where traffic moves at two different levels at one portal due to the double-deck alignment of the bridge. Originally, the roadway was comprised of brick before being replaced during the Parkway reconstruction in the 1980s.

Fort Pitt Tunnel Specifications ![]() - Pennsylvania Department of Highways

- Pennsylvania Department of Highways

The plan for a bridge and tunnel combination at the current location was derived in the 1930s. Planners then had intended for a bridge to span the Monongahela connecting what is now Fort Pitt Boulevard to a tunnel to facilitate traffic between the city and the growing South Hills. The Fort Duquesne Bridge and Fort Duquesne Tunnel, as they were called then, would have cost $8 million to construct, but lack of funding and World War II put the brakes on the project.

Even Tod and Buz from Route 66 took a ride through the newly opened tunnels

at the start of the episode "Goodnight Sweet Blues."

Construction of the final link from Churchill to the Turnpike began in 1961. Not just because of Interstate 70 being proposed through the city, but also because of the growth of Monroeville justified the construction of a bypass. The $11,124,763 section opened at 11:30 AM on October 27, 1962. It is easy to tell that this part was built after the Interstate legislation was passed because of the wide median and its six lanes.

The 1.6-mile-long, 6% grade Green Tree Hill has been a problem for trucks almost since the opening of the Parkway West. The first incident occurred on June 4, 1965 at 9 AM, when the brakes on a flat bed tractor-trailer failed as it approached the tunnel, struck three cars, and one of the steel coils it was carrying hit a fourth in the rear. Fortunately there were no injuries but James Kenner, who was at the wheel, had to be extricated from his cab and was treated at Allegheny General Hospital. Louise Ward of Mount Lebanon was treated at the same hospital after also being extricated from her vehicle which was demolished after being smashed by Kenner's truck which crashed into and cracked the tunnel's granite facade.

|

|

|

|

The next major wreck took place October 23, 1979 at 10:30 AM when another rig hauling strips of rolled steel being driven by Lynn Bradley of Phenix City, Alabama, lost its brakes and rammed into the tunnel entrance. In the process, the tractor-trailer jack-knifed and wedged a pick-up truck, which it had struck once before pinning it against the tunnel wall about 100 yards inside. Roger Carrier, the new PennDOT District 11 engineer, and Pat Wood, public information officer, were inside the offices at the western end of the tunnel when the accident took place. "We heard this loud noise and everyone went running outside," Carrier said. "The tunnel maintenance workers were already in there, and the truck drivers were already outside their vehicles." Carrier said he ordered everyone out of the tunnel after a series of small explosions, which were later attributed to backfiring of the tractor-trailer engine which stopped by the time the Pittsburgh Bureau of Fire arrived on scene. "It was like a series of shotgun blats, probably amplified because of the tunnel acoustics." Bradley was taken to Allegheny General Hospital for treatment and the pick-up driver was treated on scene. If the brakes had failed only a minute earlier, the truck might have run into vehicles on Green Tree Hill. Carrier added that PennDOT was in the process of placing more signs near the top of the hill and on a long grade near Churchill on the Parkway East to warn truckers. PennDOT was also looking into installing truck crash barriers; however, the state was hamstringed by not only money but also right-of-way in which to install them. The Department of Transportation did implement a 35 MPH speed limit for trucks descending Green Tree Hill after a rash of accidents on Green Tree Hill in the late 1970s. While trying to obtain federal funds to build a runaway truck ramp just before the Banksville Road interchange during that time, PennDOT would finally construct one in the 1980s.

The most tragic truck accident involving a truck losing its brakes took place on April 28, 1980 at 1:15 PM. A tractor-trailer being driven by Henry Young of Staughton, Massachusetts crossed the Fort Pitt Bridge and down the Liberty Avenue ramp, crashing into the First Federal Savings and Loan Association office in the Empire Building at the corner of Liberty Avenue and Stanwix Street (current location of Fifth Avenue Place). A bank teller at First Federal ran to see what happened when she heard a horn beeping. It appeared that Young attempted to avoid stopped traffic at the intersection, as the rig jumped a traffic island in Gateway Center and uprooted a tree. Ironically, he had been cited for speeding earlier that day by state police on Interstate 80. Sally Griffith, a clerk at the Pittsburgh Tourist and Convention office in Gateway Center dialed 911 as she saw the truck jump the island. "I sit here every day and watch traffic going by. Some of the big trucks, they just go flying past here off Fort Pitt [Bridge]. While he was crashing into the building, I was talking to the lady [emergency operator]. It was awful. I saw people flying, while on the phone. It was the most horrible thing in the world, but you know, it was fate; unknown people who just happened to be on that street." Thomas Bates, who was traveling up Green Tree Hill said, "He was flying, flat out moving. He was smoking brakes, I can tell you that." He added, "He was scared. The look on his face was like, did you ever see the look of someone scared out of his mind? Well, that's the kind of look he had." Richard Borland, a truck driver traveling in front of Young, said Young contacted him on the CB radio. He was told the brakes were failing. "I just broke an airline," Borland recalls the conversation. "He just lost everything."

Bernie Welborn, director of safety for the Pennsylvania Motor Truck Association, said if a driver was having a problem with their brakes passing through the tunnel and over the bridge, they would not exit and stay on the Interstate where chances of an accident would be lower. "I find it difficult to believe it was a brake line, unless it was in the copper tubing in the back," Welborn said. "If the break was in the flexible hose between the cab and the trailer, it shouldn't have happened. That's part of the driver's pre-check responsibility. I'll buy it if it was in the copper tubing." That day it would have been possible for the truck to travel down the hill, through the tunnel, and across the bridge without hitting anything since traffic was fortunately light. The scene was cleared shortly before 11 PM, roughly 10 hours after the accident.

Unfortunately, as the rig slammed into the savings and loan building, it crushed and killed three people, two of whom were sisters. Two other sisters and five others were injured. The sisters who were killed were the mother and aunt of Susan Wallace, another who was injured and lost her unborn baby in the accident. They were all in Pittsburgh two witness Susan's and her husband's graduation ceremony at the University of Pittsburgh the day before where they received doctorates in psychology, and the coming weekend was to be her baby shower.

For the first 21 years of its existence, the Fort Pitt Bridge was painted gray. It would not receive its trademark gold color until a repainting job that lasted from 1980 to 1981. The project involved cleaning the bridge surfaces to remove debris and corrosion, application of a red primer, a secondary sandstone color was applied before the final coat consisting of Aztec Gold. The price tag for the repainting job was $2.3 million and at the time was the largest bridge painting contract ever awarded by PennDOT.

A couple times during the 1980s, the term "nightmare" could be applied to a traffic jam involving an accident on the Parkway. On October 17, 1985, a five-vehicle crash shut the Fort Pitt Tunnel down for most of the day. It began at 6:40 AM, when a tractor-trailer struck a car and pushed it more than 1,500 feet into the tunnel, coming to the rest after an explosion and fire. The fire damaged the inbound tube, buckling supports, burning electrical circuits, and dropping ceramic tiles onto the road. Fortunately there were no deaths and only two minor injuries. Emergency crews had trouble getting to the site of the accident due to extreme heat and smoke. "We couldn't locate it, so we put people on safety lines, then had men work their way inside the tunnel," said John Leahy, deputy fire chief. Firefighters strung more than 2,000 feet of hose before they found the burning wreckage. The firefighters and emergency medical personnel did not have to worry about casualties because the occupants of the truck and car escaped before they were engulfed. Keith Glassburn, of Clinton, Arkansas and his wife were in the rig at the time. "I was on the inside lane, when a car starting turning onto an exit [West End], then cut out in front of me," said Glassburn. He added, "I went onto the shoulder to avoid hitting it [the car], then skidded into the guard rail." His truck careened off the guide rail into the Parkway's right lane striking a car, swerved to the left lane, then ran over the top of another automobile. "I was standing on the brakes, but it kept pushing the other auto for what seemed like a mile," Glassburn said. State police said he would be charged with failure to obey the 25 MPH speed limit for trucks with a gross weight of 21,000 pounds or more, as well as driving too fast for conditions. The outbound tube reopened at 11:35 AM and the inbound tube at 4:30 PM. Just as things were wrapping up, a truck overturned on the Parkway near the Banksville Road on-ramp when its load shifted at a bend. Then later that night, another accident happened a quarter mile from the morning accident.

The next "nightmare" occurred on October 23, 1987 when a tractor-trailer crashed and burned between the western portals just before 12:30 AM. Six vehicles including the truck were damaged or destroyed. The accident severely damaged the tunnels' electrical system, specifically the automatic carbon monoxide exhaust system and lights. The outbound lanes reopened at 8:55 PM and the inbound lanes at 10:15 PM after Duquesne Light restored power to the tunnels around 5:40 PM and Sargent Electric Coworkers managed to activate the exhaust system and lights by splicing damaged cables. "They have the system up and working. People can feel confident using the tunnels," said Dick Skrinjar, PennDOT spokesman. While the carbon monoxide monitoring and exhaust system adjusts itself according to levels in the tunnels, workers had to change the speed of the fans manually until permanent repairs were made. As for the damage to the structure itself, he added, "The entire garage is incinerated and destroyed. The equipment room and all of the electronic-monitoring equipment is destroyed." Over 12 hours after the accident, PennDOT officials went on television to encourage employers to release workers early and on a staggered schedule to avoid another snarl. The outbound lanes and the approach to the Fort Pitt Bridge were at a standstill at 4:30 PM but gone by 7:00 PM.

|

The Fort Pitt Tunnel has such a grand entrance into Pittsburgh that even KDKA-TV, which is located at the end of the bridge in Gateway Center, used it as the intro to their Eyewitness News newscasts in the 1980s. |

|

In the mid-1980s, the original Parkway was beginning to show wear. PennDOT rebuilt the entire highway, from ground up, from the Greensburg Pike interchange into downtown which equated to 6.7 miles of the highway. For a time, the westbound lanes were closed, which meant the eastbound lanes were used for two way traffic. The project included rehabilitating 21 bridges including the Squirrel Hill Tunnels and required 200,000 square yards of slip-formed reinforced concrete. This project ended in late 1985. One feature of the project was the addition of pumps in the westbound lanes between Grant Street and Interstate 279. These lanes are depressed and on the same level as the Mon Warf parking area and the Monongahela River. During floods such as in 1972 when Tropical Storm Agnes hit Pennsylvania, the parking area is always under water. If water reaches the highway, the pumps kick on.

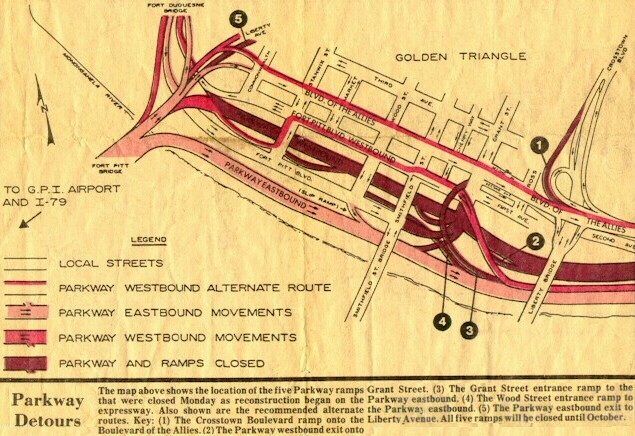

I-376 detours during the construction. (Greensburg Tribune-Review)

As mentioned above, the westbound lanes of the Parkway from Stanwix Street to Grant Street are located on the same level as the Monongahela River. Between January 19 and 21, 1996, these lanes were closed down because of flooding. The rare January thaw due to temperatures into the 60s caused tremendous run-off from melting snow flooded many low lying areas including the Point.

Out of all of the people driving the Parkway on October 25, 2000, Anisa Hadiya Abdul is a unique commuter. The reason being is that came into the world just a little after midnight on that day right at the Oakland interchange. Aleeshea Cosby, mother, was leaving her job at University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and was heading home. She began having pains, but did not think anything of it since she was due on November 17. Aleeshea called a friend, Sylvia White, to tell her she was going to the hospital and she might need her as a backup driver. Good thing, because her services were needed. Sylvia entered the Squirrel Hill Tunnels driving with a mother-to-be and exited with a woman in labor. White managed to pull over and to wait for city paramedics; however, little Anisa was not so patient. The 6-pound, 12-ounce baby girl measuring 18 1/2 inches long and in perfect health came before the paramedics could get to the scene.

If you were traveling the Parkways on January 11, 2001, you have my sympathy. On that day, not one but two trucks ended up getting lodged in both the Squirrel Hill and Fort Pitt Tunnels and during both rush hours. This is not the first time a truck has become wedged in either tunnel as it has happened many times over the years; however, it was the first time where it happened twice on the same day. The incident on the Parkway East started when an Ontario truck driver got his tractor trailer stuck in the Squirrel Hill Tunnel at 3:45 PM. The driver assumed that his rig would fit through the tunnel since the overheight truck warning signals did not flash, which were shut off due to mechanical problems. However, Officer Ramon Paul of the Pennsylvania State Police said that his truck was actually 14 feet, four inches; 10 inches too tall. At about 100 feet into the tunnel, the trailer became wedged against the ceiling. The driver then proceeded to back the vehicle out which added to the problems when the drive shaft broke. The first attempt to dislodge the trailer by letting the air out of the tires worked, but the trailer could only be pulled by a tow truck inches at a time. The second attempt did the trick when the towing company first pulled the trailer off the tractor and then both out shortly after 7:00 PM. By 7:20 PM, the line of vehicles that stretched all the way to Monroeville were finally moving once again.

Another unfortunate incident happened on January 28, 2001 when a tour bus heading from Steubenville, Ohio en route to the Seven Springs ski resort flipped over as it turned to head toward the Turnpike's toll plaza. Only a few were injured which was surprising because the bus slid off the highway into a wooded area off the shoulder.

The exit renumbering that took place on I-376 in the summer of 2000 was not the first for one segment of the expressway. In 1964, when the designation changed from I-70 to I-76 from the Point to the Turnpike, so did the exit numbers to commence the numbering sequence. The numbers began with Exit 22 at Stanwix Street and ended with Exit 37 at Murrysville, and afterwards Stanwix Street became Exit 1 and Murrysville became Exit 17. This sequence continued after the designation changed to I-376 in 1972.

With a highway as old as the Parkway, problems usually arise. One such problem is the cracking and shifting of a concrete retaining wall that supports the expressway's eastbound side between the Boulevard of the Allies and Bates Street. Fred Reginella, City Director of Engineering and Construction, who toured the site with PennDOT engineers in December 2001 said, "It's alarming." PennDOT District 11 Engineer Ray Hack said, "We've been monitoring the wall since summer and it's moving faster than we'd like." As a result, Hack asked the Department of Transportation administrators in Harrisburg to authorize $350,000 in extra funds for emergency repairs, and the request was granted. The 150 foot-long section was discovered in summer 2001 by PennDOT maintenance workers who noticed minor subsidence on the shoulder and slight shifts to the Jersey barrier that runs along the side of the expressway. From below the evidence is more convincing, as large pieces of concrete now lay on the ground next to the base of the wall. The contractor in charge of the repairs will drill through the wall and insert large bolts into the earth, known as "rock anchors" which might mean the closure of the far right lane at times. Hack also mentioned that the northern terminus of the Mon-Fayette Expressway is proposed to connect to the Parkway near this area, and that the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission would be responsible for construction of a new wall.

One problem that was facing the City of Pittsburgh was that eastbound lanes of Fort Pitt Boulevard were crumbling. It was so bad that you could see exposed rebar driving along the highway. Also, due to years of use, the lanes began to sink forming sunken areas where water would pond in heavy rains. One of the only places where an elevated highway would flood. Because of the decrepit nature of the eastbound lanes, a detour was put in place for vehicles weighting more than eight tons. Traffic was also a problem on the Boulevard, because it was the only connection from I-279 south to I-376 east. A proposal to rebuild the eastbound lanes and to construct a direct connection to I-376 east was arranged. The project began in early 2002 with the demolition of the elevated lanes. The Interstate Connector opened on December 6, 2002 at 11 AM.

While the last leg of rehabilitation of the Fort Pitt Bridge and Tunnel were taking place, work was also performed on the segment of the Parkway from the bridge to Grant Street. Construction began on April 6 to replace the elevated section which spans the Mon Wharf Parking Lot, and the section under the Smithfield Street Bridge. This section reopened to traffic on October 1, 2003.

View of the elevated lanes being rebuilt during the Fort Pitt

rehabilitation. (PennDOT)

More flooding affected the Parkway from Stanwix Street to Grant Street on November 20, 2003. The rising water was caused by a heavy line of rain showers that blanketed western Pennsylvania a day earlier. The closure of the lanes at evening rush hour caused gridlock in downtown Pittsburgh, with back-ups stretching all the way out to the Edgewood/Swissvale interchange. The lanes reopened to traffic on November 21.

With all of the flooding affecting the "bathtub" section (Grant Street to I-279) of Interstate 376, Pittsburgh Councilman Doug Shields has drawn up legislation to remedy the situation. The resolution asks PennDOT to "act immediately to resolve this matter with the appropriate solution, including but not limited to extending the height of the apparently too-low flood wall." When the expressway closes, the city has to deploy more police to handle the resulting traffic congestion. The problem is when the river reaches 21 feet, the gravity drain system's valves are closed to prevent water from backing up and flooding the Parkway. Any water that accumulates on I-376 flows into a basin where two sump pumps send it back to the river. If the river level gets to 25 feet, nothing can keep the roadway clear. The wall can't be made higher because engineers determined that six feet is as high as they could go without the whole section of expressway floating like a barge due to hydrostatic pressure. However, the section has a good track record of staying open when the Mon Wharf parking area is usually closed. The level of the Parkway can't be raised either because the minimum height clearance for Interstates is 17 feet-6 inches and there is no room to do that between Grant Street and the Fort Pitt Bridge.

Aerial footage of flooding on January 26, 2010.

After the rehabilitation of the Fort Pitt Tunnel just concluded, you'd think there would be no problems, right? Water began leaking into the tunnel during the last week of January 2004, at the northbound portal on the south side of the tunnel. The water was suspected of coming in between the inbound and outbound sides. PennDOT crews continued to salt the roadway until permanent repairs were made.

On October 17, 2005, US Senator Rick Santorum and US Representative Melissa Hart made an announcement at Pittsburgh International Airport that has been years in coming. By January 1, 2009, the Interstate 376 designation will be extended westward to the airport and back to I-76 at the New Castle Interchange. Improvements to the associated expressways such as the cloverleaf at PA 60 and the designation change were included in the "Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users" highway reauthorization bill passed two months earlier. Cost for the extension is estimated at $80 million to bring the expressways to Interstate Standards, but doesn't have to be completed for 25 years and certainly not by the target date of New Year's Day 2009. The first section to see the new designation was from I-79 to I-279 when the change became official on June 10, 2009. For a time, I-279 and I-376 shields adorned the "totem pole" assemblies lining the roadway. Approximately $40 million was spent to upgrade the route to Interstate standards, including the reconfiguration of the US 22/US 30/PA 60 interchange at Robinson Town Centre. The cost could have been $190 million if PennDOT had not received design exceptions to keep several overpasses that don't comply with the 16-foot, 6-inch vertical clearance requirement. The designation was officially extended from I-79 west to I-80 in Mercer County on November 6, 2009.

Another year and another overheight truck gets jammed in the Squirrel Hill Tunnel. On April 2, 2006 at 4 PM, a dump truck pulling a trailer with a backhoe ignored three electronic warning signs indicating his truck was taller than the tunnel ceiling. The driver even ignored a PennDOT worker dressed in bright yellow who was jumping up and down and waving his arms at the tunnel entrance. The arm of the backhoe hit the ceiling causing minor damage, but the impact sheared the hydraulic line. Even though traffic backed up to Downtown, most drivers took it in stride. State Police rerouted eastbound traffic across the median at the tunnel's western portal and sent it back towards Downtown. PennDOT workers deflated the truck's tires and removed it by 5:30 PM which allowed the left lane to reopen while clean up took place of hydraulic fluid spill. The right lane reopened by 6 PM.

In the post-September 11 world, everything seems to be a target including the tunnels in Pittsburgh. They became the target of a bomb scare on June 1, 2007 when a call was made at 5:45 PM to Allegheny County 911 from a pay phone at Carson Street and 12th Street on the South Side. State Police and PennDOT closed the Squirrel Hill, Fort Pitt, and Liberty Tunnels. Traffic was at a standstill as police turned vehicles around at the portals. After security sweeps, the Squirrel Hill Tunnel reopened at 6:20 PM and the other two a half hour later. The FBI is now involved with the case and the phone where the call originated has been confiscated.

Many solutions have been proposed over the years to ease the bottlenecks on both sides of the Squirrel Hill Tunnel, from boring another tube to cutting away the hillside, to banning trucks at rush hours. Enter the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission's newest entry: build elevated toll lanes between Downtown and Monroeville. CEO Joe Brimmeier said in February 2008, "I threw it out there for its potential to get something done very quickly to bypass [the ground-level congestion at] the Squirrel Hill Tunnel. PennDOT already owns the right of way and we would find a way to tie it into the Mon-Fayette Expressway." He added the toll lanes could be an option to building the Turtle Creek-Monroeville leg of the Mon-Fayette Expressway, and no engineering studies have been done to determine if the expressway would go through, over, or around the hill that the Squirrel Hill goes through. Lane usage would be similar to other cities where HOT (high occupancy toll) lanes exist, with higher tolls during the rush hours and lower ones in non-peak hours. The proposal caught the Department of Transportation, and others, by surprise. Secretary of Transportation, and one of five members of the PTC board, Allen Biehler said in response, "The days of just willy-nilly throwing out concepts of decks over the Parkway and bypasses of the Squirrel Hill Tunnel without a thorough analysis are over. If someone wants to have incredible dreams about transportation, how about focusing on public transportation and doing things that make that option more viable for more people?" Representatives Nick Kotik of Robinson and Tom Petrone of Crafton Heights were shocked by the idea of elevated toll lanes. "It's far-fetched. It boggles my mind," said Petrone and Kotik replied, "In theory, it sounds nice, but where would the money come from to fund this? We have projects that have been on the books for years." Their colleague Representative Rick Geist of Blair County, and the ranking member of the House Transportation Committee, thought otherwise and that elevated lanes "make a lot of sense as a public-private partnership." However, he said he'd prefer the state Transportation Commission, not the Turnpike Commission, handle talks with a private firm who would handle construction and collect the tolls. The Parkway East "isn't even part of the Turnpike Commission's charter," he said, referring instead to the ones under their jurisdiction, but added that the PTC's scope of responsibility could get changed by the General Assembly. Representative Geist said the lanes could use "time-of-day pricing," meaning the toll would be higher during the rush hours and lower during non-peak hours.

One issue with the burgeoning Robinson area has been the inadequate junction of the major routes that crisscross the Township. Since construction in the 1950s, the interchange where the Parkway and Steubenville Pike intersect has been a cloverleaf. However, as traffic has grown with the township, so has lane-changing and weaving at that location. The $13.7 million project began on June 8, 2009, as part of the conversion to Interstate 376, to eliminate the dangerous situation by reconfiguring the interchange. The project also included resurfacing, bridge improvements, wall construction, drainage improvements, new guide rail, curbing, highway lighting, and signing. Once completed in , the first American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, or federal economic stimulus transportation funded project in Allegheny County, saw the western and eastern loops removed and replaced with signalized at-grade intersections to replace the former ramps. On March 5, 2012, PennDOT announced that it won the 2012 Diamond Award Certificate for Engineering Excellence in Transportation from the American Council of Engineering Companies of Pennsylvania (ACEC/PA).

Pittsburgh welcomed the world in September 2009 when President Barack Obama hosted the G-20 Summit at the David L. Lawrence Convention Center. Due to the heads of state traveling from the Pittsburgh International Airport into downtown, the Penn-Lincoln Parkway between was closed for each motorcade arriving on September 24 and departing on September 25. In addition, ramps to and from Interstate 376 in the Golden Triangle were closed to all traffic except for emergencies.

The concept of "bridge freezes before road surface" has been demonstrated numerous times on the Penn-Lincoln Parkway just to the west of the Carnegie interchange, below the Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad trestle. That 622-foot-long bridge was the site of 132 crashes over a 12 year period, due to it being sloped and on a slight bend, so PennDOT installed an automatic anti-icing system on the bridge in Summer 2010 as part of a $5.4 million project to rehabilitate that as well as two other Parkway bridges in the area. The system is comprised of sensors that measure the temperature of the bridge deck and air, and when needed, activates a pump that sends a brine solution through a network of spray disks embedded in the bridge as a temporary solution until a plow or salt truck can arrive. Improvements to the bridges begun in May 2010, with work initially occurring underneath the bridges. In June, replacement of bearings and pedestals on the bridges, which required jacking the spans to remove the old, took place. In July, expansion dam replacement on the bridge over Bell Avenue and Arch Street took place, with the installation of the spray disks for the anti-icing system took place in August.

Deer are the typical animal that emerge from Pennsylvania's woodlands onto the highways, but during the summer and fall of 2010 another four-legged creature was making an appearance. Two cows that kept escaping from a local farm near Interstate 376 in Beaver County, were appearing on the eastbound side between Exit 36 and Exit 38.

Starting at 6 AM on May 9, 2011, drivers on the Parkway East got a little help with travel from above. It was at that time when PennDOT began providing estimated travel times between various points on the variable message boards for travelers between downtown Pittsburgh and Monroeville. "By having this real-time information displayed on message boards, motorists will be better able to predict how much time it might take to reach their destinations, and, during times of heavy traffic, possibly consider alternate routes," said Dan Cessna, PennDOT District 11 executive.

It was lights, camera, action on the Parkway West during the nights of May 25 and May 26, and mornings of May 26 and May 27, 2011 for filming of the motion picture The Perks of Being a Wallflower. The Interstate was closed at those times from the Carnegie interchange eastward to downtown, including the Fort Pitt Bridge and Tunnel.

Landslides are a problem for the Schuylkill Expressway in Philadelphia, but not so much for the Penn-Lincoln Parkway until January 27, 2012. Mud, rocks, and debris including a tree came tumbling down onto the expressway around 9:30 AM near the westbound entrance to the Squirrel Hill Tunnel and closing one lane for most of the day. A crew had to remove four large trees before geotechnical engineers could even inspect the hillside's stability. PennDOT assessed the hillside the following week to determine if more material needed to come down and whether permanent barriers were needed.

One aspect of driving in Pittsburgh is dealing with traffic slowing down for tunnels, and PennDOT began work on March 19, 2012 to alleviate that at one of them. A $49.4 million rehabilitation project began on the Squirrel Hill Tunnel that would include raising the height of the tunnel by removing the ceiling and ventilation corridor above. That corridor was designed to maximize the flow of exhaust and air out of the tunnel with fans pulling that air from slots in the roof, but recent studies showed the false roof was unnecessarily. "The belief is if we can open that up with a higher clearance and improve the lighting, people won't feel like they have to slow down" as they enter the tunnels, PennDOT Spokesman Jim Struzzi said. The cellular and radio transmitters, that provided commuters with service through the tunnels, were shut down in June 2012 because of their being located above the former ceiling. The project included updating electrical, lighting, control, and ventilation systems, AM/FM and cellular transmitters, structural repairs to the walls and arched ceiling, installation of a water line, new road surface, temperature and carbon monoxide monitors, CCTV cameras, fire extinguishers and communication devices, and a new overheight truck detection system for the westbound lanes. Also included was rehabilitation work on the bridge that carries the Penn-Lincoln Parkway over Commercial Street just east of the tunnel and replacement of expansion dams on ramps at Exit 77. The project came to an end in the summer of 2014.

Improvements to the New Castle bypass began in Spring 2012, which focused on bridge preservation, roadway reconstruction, concrete patching, asphalt overlay, and guide rail and drainage improvements, overhead sign structure replacement, and other improvements from US 422 to US 224. The $17.9 million project concluded in Summer 2013.

A project resurfacing ramps connecting the Fort Pitt Bridge to various roadways began the night of April 16, 2012. The $8.7 million project took place on roughly 20 ramps as well as a part of the Penn-Lincoln Parkway in the "bathtub" section in downtown and concluded in Fall 2013.

In May 2012, the three-mile section of Parkway West between Green Tree and the Fort Pitt Tunnel earned a dubious title. A study performed by traffic information company INRIX named that section of expressway the ninth most congested corridor in the country, and to put it in some perspective, the top eight spots were all in New York or Los Angeles. The study suggests the average commuter spends at least nine extra minutes, or 36 hours a year, sitting in gridlock. But all is not lost, as PennDOT Spokesman Jim Struzzi commented on the story by saying, "We are in the process of conducting a study to look at options that may be able to alleviate some of the congestion to keep things moving more steadily during the AM/PM rush hours."

Allegheny County Executive Rich Fitzgerald proposed his own idea to solve the congestion problem at the tunnel: build another tube. "I don’t think it’s anything that would be built in the next year or two, but we need to figure out a way to ease the traffic congestion in that corridor. As a long-term planning issue, it’s critical," Fitzgerald said on December 4, 2012. He suggested the third tube option at two separate forums sponsored by the Community College of Allegheny County and Urban Land Institute. Kent Harries, associate professor of structural engineering and mechanics at the University of Pittsburgh, expressed concerns about the idea that could cost hundreds of millions of dollars. "You would have a number of serious impacts," Harries said, noting that a project would require improvements on both sides of the tunnel to prevent shifting the bottleneck from one location to another.

One animal that wasn't caught up in the gridlock was a baby pig. On the morning of May 30, 2012 between 8:30 AM and 9 AM, motorists reported seeing a pig wearing a scarf walking along the jersey barrier west of Exit 67. State troopers from the Troop B barracks in Moon Township also spotted the pig, but were unable to catch it before it scurried off into the woods. It is believed that the baby pig is a pet belonging to someone who lives along that section of the Penn-Lincoln Parkway.

Prayer is something drivers along the Parkway might rely on, and they probably don't know that someone is looking over them. Since 1956, an unofficial Pittsburgh landmark known as "Our Lady of the Parkway" has overlooked the expressway from its perch in South Oakland, right above Exit 73. When a woman who has taken care of the shrine, which includes a statue of the Virgin Mary, noticed another statue missing in August 2012. A prayer vigil was held on August 22 in hopes that the statue would be returned by then.

Something that has been living on a wing and a prayer is the ramp meter implementation plan that has been discussed for years. It returned to the forefront in August 2012 when PennDOT announced it had completed a new traffic study, which took ideas from other congested cities and applied them to Interstate 376 from downtown to the Turnpike. The plan calls for closing or metering on-ramps during peak travel times, and would affect the Bates Street on-ramp to I-376 eastbound, Beechwood Boulevard, South Braddock Avenue, Ardmore Boulevard, and Greensburg Pike on-ramps to I-376 westbound. Indications are that these improvements would decrease drive times by five to six minutes and lessen the probability of accidents.

Routine maintenance perhaps avoided a serious accident in the Fort Pitt Tunnel on March 14, 2014. Crews discovered a section of the concrete ceiling was sagging in the eastbound tunnel around 9 AM, prompting PennDOT to close one lane for most of the day and then the entire tunnel after 9 PM. Workers removed a 10 foot by 30 foot section of the ceiling that began to sag due to deteriorating support brackets. The emergency repairs were completed by Saturday morning, and the tunnel reopened at 4 AM, just in time for traffic heading into Pittsburgh for the Saint Patrick's Day parade. Just as had been done in the Squirrel Hill Tunnel, PennDOT decided that instead of repairing the tunnel ceiling that they would remove the entire structure. Starting on the weekend of November 15, 2014 and for the following seven weekends, work took place to demolish the westbound tube's ceiling with demolition work in the eastbound tube beginning in December 2014. The $21 million project also included relocation of CCTV cameras and tempature monitors, removal of air duct light fixtures, receptacles, and microwave traffic detectors, conduit strut supports, minor structural repair work to the walls and air duct arch, waterline and standpipe, as well as milling and resurfacing the roadways. The entire project was completed on May 27, 2016.

At the same time, the entire section of the Parkway West from Interstate 79 to the Fort Pitt Tunnel was undergoing a $72.8 million rehabilitation project. Begun in Summer 2014, work entailed adding a fourth lane westbound between Rosslyn Farms and Interstate 79; lengthening ramp deceleration lanes at the Carnegie exit and acceleration lanes from Interstate 79, Poplar Street, and Greentree exits; preservation of 15 bridges, three culverts, and the roadway; deck replacement on the Carnegie bridges; drainage improvements; guiderail upgrades; signing and pavement markings; concrete median barrier replacement; sign structure rehabilitation; shoulder reconstruction; and milling and resurfacing the roadway. Structure painting was the last phase of the project which wrapped up in Summer 2016.

The lighting on the Parkway West could have used a make over as well, as deficiencies in the system began to come to light (no pun intended) in November 2015 after the change to Standard Time. However, PennDOT District 11 Executive Dan Cessna mentioned that the issue began a month prior. "We’re working on it," he says. "It’s a number of problems, some of it related to the age of the system, and some of it related to construction damage, which we are working on at this time." Two crews were assigned to get the lights back on quickly, with some of the lights from the tunnel to Green Tree restored by the November 4 evening rush hour.

Not related directly to the Parkway East, but something happening directly above it took place on December 28, 2015. On that day, the Greenfield Bridge, which had spanned the Parkway just west of the Squirrel Hill Tunnel and interchange in Pittsburgh, was imploded. In preparation for the demolition, PennDOT closed the Parkway the day before to begin covering the roadway with dirt to cushion the fall of debris. After the demolition was delayed 20 minutes because a person was spotted in the "exclusion zone" nearby, the bridge was imploded at 9:20 AM and came down in only 10 seconds, taking out the smaller one constructed underneath. Even though Mosites Construction was required to have the expressway reopened by 6 AM on New Year's Day to accommodate traffic to and from the First Night celebrations downtown, crews had it reopened by 3 PM the day before. The week between Christmas and New Year's Day was picked for the demolition because it is the week with the least amount of traffic. A shoulder crack and some chucks of concrete were taken out of the median barrier, it appeared the Parkway faired well, but even with the "bed" of dirt laid on the Parkway, a dip in the right two westbound lanes and the far right lane eastbound were discovered. Dan Cessna of PennDOT said it is not a hazard and "If it crushed the base, there’s a failure of the base, then we would need to dig down and actually reevaluate the pavement structure underneath, or if we just need to resurface at the surface level." By the late 1980s, time began to take its toll on the bridge. One day, large chunks of concrete began to fall onto the Parkway with numerous vehicles becoming damaged; fortunately, not many people were injured. PennDOT's response to this was to string large nets around the supports of the bridge, which were still in place until it was demolished. In the late 1990s, with a rehabilitation project planned, a bridge was built beneath the span to catch debris and other items that would have fallen which also remained until the bridge's ultimate demise.

Residents of Ivy Lane and Pine Street in Center Township, Beaver County, were awoken on the morning of September 10, 2018 to a deafening sound. It turned out to be a rupture around 5 AM of a 24-inch gas pipeline which shot flames high into the air. Even before first responders could contact Energy Transfer Corporation to alert them of the explosion, sensors had detected the problem and began to shut down the flow of gas but not before one home was lost. The fire caused a high tension transmission tower nearby to buckle due to the heat, taking five others with it in a chain reaction which caused the power lines to sink lower towards the Beaver Valley Expressway. Interstate 376 was closed a just before 7 AM between the Center and Aliquippa interchanges and remained so until a little after Noon to repair the lines. It was determined that the rupture was caused by a landslide due to heavy rains during the previous weekend.

Drivers doing stunts on public roadways have seemed to escalate since the COVID-19 pandemic, and Pittsburgh is not immune. On the morning of July 21, 2023, around 50 cars were drag racing and performing burnouts on the upper deck of the Fort Pitt Bridge, and upward of 300 people were involved. Just after 3:35 AM, multiple reports were received of traffic stopped and drivers performing said stunts. "This is the first time we’ve seen anything this year where they’ve actually taken over a whole bridge," said Pennsylvania State Police Troop B Public Information Officer Rocco Gagliardi of the Pennsylvania State Police. "They were actually seeing all these people on top of the bridge recording and then people trying to get through that bridge were calling into the 911 center saying, 'Hey I can't get through, I'm stuck in the tunnel,'" said Trooper Gagliardi. When troopers arrived on the scene, a burgundy Jeep Grand Cherokee hit a police unit and then nearly struck two troopers. "This is the first time we've seen anything this year where they've actually taken over a whole bridge, and that's a huge safety concern because if you are coming out of that Fort Pitt Tunnel, and then you are at a complete gridlock with 50 cars doing donuts and drag racing both directions — it's only a one-way bridge. If you're coming through there for an early work shift, you're looking at something potentially fatal," Gagliardi said. On the following Sunday, Jason Stotlemyer of Bridgeville was charged by state police with felony counts of aggravated assault, aggravated assault with a vehicle and fleeing or attempting to elude police; and misdemeanor counts of simple assault and causing an accident involving damage to an occupied vehicle. He is no stranger to police as he has racked up 24 traffic citations since 2018. On July 25, another man, Graham Carvins Liberal of Sunrise, Florida, was charged with recklessly endangering another person, riot, disorderly conduct and walking on a highway. He was arrested at Pittsburgh International Airport as he was heading back home to Florida. According to court documents, Liberal arranges what are known as "pre-planned car meets" via social media.

Trucks striking overpasses is nothing new in Pennsylvania, and the PA 318 overpass on Interstate 376 would not remain unscathed. Shortly before 10:51 AM on December 7, 2023, Mercer County 911 received word of the accident, a roll-off truck struck the overpass while traveling eastbound. While the truck was not carrying a container at the time, the truck's hydraulic bed was raised and it hit the bridge as the truck passed underneath. The raised bed ripped through two support beams and damaged a third, then penetrated a couple of feet through the road surface, leaving only two of the five support beams unaffected. The bed eventually separated from the truck, and the driver ended up being severely injured. He was taken to Saint Elizabeth Hospital in Youngstown, Ohio. The bridge was closed and Interstate 376 eastbound traffic was detoured through the off- and on-ramps at the interchange rather than continuing underneath the damaged bridge. PennDOT inspection crews determined that the damaged section would need to be removed rather than repaired. Work to do so began the following morning and was completed the same day.

"We are moving at light speed as far as PennDOT is concerned,"’ said PennDOT project engineer Mark Nicholson. Unlike the previous span, the overpass will be two and one-half feet higher and be comprised of steel rather than concrete. "Using steel rather than concrete will make it easier to raise the bridge," said Richard Schoeder, an engineer with Michael Baker International. While no bonuses will be given for early completion, daily penalties in the range of thousands of dollars will be assessed against the contract for each day it is late in opening. PennDOT is seeking to recoup costs of the replacement from the trucking company.

Removal of the span over the westbound lanes happened on April 21, 2024. Placement of the beams for the new overpass took place overnight from Friday, June 14 into Saturday, June 15, which also required the closure of Interstate 376. The expressway reopened Saturday morning, 40 hours earlier than expected.

Aside from the bridge replacement, the project will also include reconstruction of a portion of three of the interchange ramps, drainage upgrades, guiderail replacement, roadside signage, and pavement markings. Minor shoulder improvements and roadway repairs to Interstate 376 under the new bridge will also be completed. The former bridge, built in 1966, had a clearance of 14 feet-2 inches, while the new bridge will meet the current standard of 16 feet-6 inches. To raise PA 318's profile in order to meet the new vertical clearance, the exit ramps were closed on June 20. The westbound lane of the bridge opened on August 26, 2024, but the eastbound on and off-ramps and westbound off-ramp at the interchange reopened four days earlier. On September 20, the eastbound lane of the bridge and westbound on-ramp reopened. The official end to the project was marked on October 4 with a ceremony attended by local officials and industry partners. "Roads like Route 318 to the vital economic stability and quality of life of the communities they serve, such as West Middlesex," said PennDOT Secretary Mike Carroll. "When an emergency forces the closure of a bridge on these community lifelines, it is a priority for PennDOT and Governor Shapiro to get them replaced, repaired, and reopened as quickly as possible. Here in Mercer County, our team was able to accomplish that in less than a year."

Travelers on the Interstate on December 22, 2024 saw a fellow traveler using a vehicle not used for highway travel. Jesse Langenhahan, a veteran pilot for 22 years, was performing some aerobatics in his single-engine Fergus SC-1 when he began noticing it not running as usual. "Between one of my sequences, I was just climbing back up to altitude and straight and level. And as I got within about 500 feet of my altitude, I felt like a little bit of power loss," Langenhahn said. He wasn't worried, but moments later, he lost power again. "Was still turning, still had fuel pressure and oil pressure," Langenhahn said. He still had fuel, but he knew the plane wouldn't make it over the trees to the Beaver County Airport.

Langenhahan looked for an opening in traffic to perform an emergency landing. "My focus was trying to land with traffic and hope that the people in front didn't hit their breaks and the people behind me would stop and give me a little bit of a gap," Langenhahn said. Around 12:45 PM, he landed in the eastbound lanes just south of the interchange with the Pennsylvania Turnpike, and then onto the shoulder as travelers and first responders showed up. "I'm happy the way it turned out. I was OK, plane's fine, minus whatever caused the power loss. But we're all in one piece so that's good," Langenhahn said. Later that day, he towing service provider for that section of the Turnpike System loaded the plane onto a flat bed, but due to its over 17-foot-wide wingspan, Turnpike officials and Pennsylvania State Police troopers escorted the truck back to the Beaver County Airport.

Links:

Exit Guide

Interstate 376 Business Routes

Interstate 376 Ends

Interstate 376 Pictures

Future Interstate 376 Corridor Map

Toll Interstate 376

Field Notes-Squirrel Hill Tunnel and Penn Lincoln Parkway East - Bruce Cridlebaugh

Fort Pitt Boulevard - Bruce Cridlebaugh

Fort Pitt Bridge - Bruce Cridlebaugh

Fort Pitt Bridge - Brookline Connection

Fort Pitt Tunnel - Bruce Cridlebaugh

Fort Pitt Tunnel - Brookline Connection

The I-279/376 Downtown Connector - Adam Prince

Interstate 376 - Andy Field/Alex Nitzman

Interstate 376 - Scott Oglesby

Interstate 376 Pictures - Andy Field/Alex Nitzman

Interstate 376 Pictures - Steve Alpert

Penn-Lincoln Parkway East Structure Tour - Bruce Cridlebaugh

Squirrel Hill Tunnel - Bruce Cridlebaugh

INFORMATION

INFORMATION

Western

Terminus:

I-80

at Exit 4 in

West Middlesex

Eastern

Terminus:

I-76/PA Turnpike at Exit 57 in

Monroeville

Length:

84.70

miles

National

Highway

System:

Entire length

Names:

Beaver Valley Expressway:

Exit 1 to Exit 15 and Exit 31 to Exit 50

Benjamin Franklin Highway: Exit 12 to Exit 15

James E. Ross Highway: Exit 15 to Exit 31

Southern Expressway: Exit 50 to Exit 57

Airport Parkway: Exit 57 to Exit 60

Penn-Lincoln Parkway: Exit 60 to I-76/PA Turnpike

Parkway West: Exit 57 to Exit

70

Parkway Central: Exit 70

to Exit 74

Parkway East: Exit 74 to I-76/PA

Turnpike

SR

Designations:

0376

7376: Exit 15 to Exit 31

Counties:

Mercer, Lawrence, Beaver, and Allegheny

Multiplexed

Routes:

US 422: Exit 12 to Exit 15

US 22: Exit 60 to Business US 22

US 30: Exit 60 to Exit

78A

US 19: Exit 69A to Exit

69C

Truck US 19: Exit 69B to Exit

70C

Former

Designations:

PA 28 (1951 - 1961):

Exit 65

to Exit 69C

PA 80 (1951 - 1961): Exit

78B to Exit

80

Alternate US 19 (1960 - 1961): Exit 69C to Exit

70C

I-70 (1960 - 1964):

Exit 64A to I-76/PA Turnpike

PA 60 (1962 -

2009): Exit 57 to Exit 60

I-79 (1964 - 1972): Exit

64A to Exit

70C

I-76 (1964 -

1972):

Exit 70C to I-76/PA Turnpike

PA 18 (1968 - 1978): Exit

1C

to Exit 2

I-76 (1972 - 1973): Exit

64A to Exit

70C

I-279 (1973 - 2009): Exit

64A to Exit

70C

PA Toll 60 (1991 - 2008): Exit 15 to Exit 17

PA 60 (1992 - 2009): Exit 50 to Exit 57

PA Toll 60 (1992 - 2008): Exit 17 to Exit 31

PA Turnpike 60 (2008 - 2009): Exit 15 to Exit 31

Former LR Designations:

1023: I-80 to Exit 15 and

Exit 31 to Exit 50

1057: Exit 50 to Exit 60

765: Exit 60 to Exit 69C

766: Exit 69C to Exit 70

764: Exit 70 to Exit 73

763: Exit 73 to Exit 79B

187: Exit 79B to Exit 80

187 Parallel: Exit 80 to Exit 85

Emergency: