Pennsylvania Turnpike

Pennsylvania

Turnpike

Referred to as "America's First Superhighway," it is strange to think that the Turnpike had its roots in another form of transportation: the railroad. William H. Vanderbilt proposed an idea to build a railroad from Harrisburg to Pittsburgh that would be under his control, and not that of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

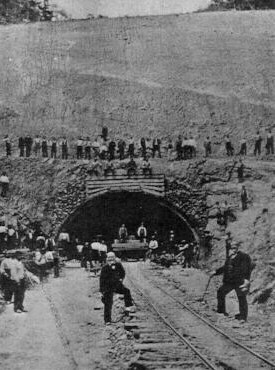

After the surveying was complete, work began on a two-track roadbed with nine tunnels. Excavation began on the tunnels in early 1884. Thousands of workers dug the tunnels for $1.25 for a 10 hour day. The construction continued through 1884 and 1885; however, trouble for the project was starting in New York. Banker J. Pierpont Morgan won a seat on the board of Vanderbilt's New York City & Hudson River Railroad. Morgan with the President of the NYC&HRRR sold the right-of-way to George B. Roberts, President of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Work stopped immediately. A total of $10 million had been spent and 26 workers lost their lives. The unfinished project came to be known as "Vanderbilt's Folly."

Andrew Carnegie visits the Rays

Hill Tunnel work site.

(Pennsylvania State Archives)

A part of the right-of-way was used for the Pittsburgh, Westmoreland, and Somerset short line railroad. The PW&S even completed one of the nine tunnels. None of the other tunnels had been finished, but some workers say that some were close enough to hear crews in the other section. Most of the line reverted to nature with water filling many of the tunnels. One of the engineers said this on the demise of the line: "And here, for the time being, and probably for a long time to come, is smothered the best line of railroad between the Ohio Valley and the Atlantic that has ever been or can be projected, built, or operated."

Some of the graded roadbed utilized by

a short line

railroad near Somerset in 1885.

(Pennsylvania State Archives)

Links:

South Penn Railroad Right of

Way

Pittsburgh, Westmoreland, &

Somerset Railroad and South Penn Railroad Grade - Russell Love

The twentieth century came and with it a new form of transportation: the automobile. Pennsylvania was one of the first states to establish a highway department. In late 1934, an employee with the State Planning Board named Victor Lecoq and William Sutherland of the Pennsylvania Motor Truck Association proposed the idea of building a toll highway utilizing the old roadbed and tunnels left behind. With these two gentlemen and with newly elected Representative Cliff S. Patterson, the idea became reality. On April 23, 1935, he introduced House Resolution # 138 to authorize a feasibility study.

Preliminary work inside

the Tuscarora Mountain

Tunnel on January 24, 1938.

(Pennsylvania State Archives)

Construction was proposed to cost anywhere from $60 million to $70 million. The surveyor's report was favorable and upon receiving this news, Governor George Earle signed Act 211 on May 21, 1937. This legislation enacted the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission. On June 4, the initial commission members were named.

The valley between the Blue and Kittatinny

Mountains as it appeared on November 5, 1937.

(Pennsylvania State Archives)

Although financing had yet to be completed, the first contract to be awarded was to Pittsburgh contractor George Vang. This was for removal of the water from the existing tunnels. The final federal approval for financing came on October 10, 1938. Four days later, the first contract for construction of the highway was advertised for bids. The contract, which covered a 10 mile stretch in Cumberland County, was awarded to the L.M. Hutchison Company of Mount Union, Pennsylvania. The problem was that there was not a single stretch of right-of-way purchased. That problem was resolved when the Turnpike's General Counsel, John D. Faller, traveled to Cumberland County to talk to the farmer whose land was proposed as the future right-of-way. Mr. Faller, and the representatives from the Public Works Administration and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, came to the site were the ground breaking would take place. There were 200-300 farmers and neighbors standing around. The gentlemen spoke to the wife of the farmer who owned the land. She agreed to sell the tract to the state. Afterwards she wanted their autographs. When Mr. Jones asked why, she said: "Mr. Jones, I want these autographs so that my children can say that they saw history being made that day when the greatest highway, a new era of road building, was started."

|

|

|

|

Until the first shovels of dirt were thrown, the PTC relied on funds from the federal government, the Department of Highways, and loans from engineers from private industry. At first, Chief Engineer Samuel W. Marshall supervised 115 engineers, but within three months that number grew to more than 1,100. The added staff was necessary for the Commission to meet the construction-season cycle and the deadline for completion set by the federal government. The planners figured on a three-four year construction period, but in the approval of the $29 million grant, the Public Works Administration set a completion date of May 1, 1940 (moved to June by a later amendment), by which the highway should be "substantially complete." This meant the PTC had a short 20 month deadline to by which to complete a large public works project.

Commission officials meet on October 10, 1938. From left to right:

Commission nominee Edward N. Jones, Commissioner Frank Bebout,

Chief Counsel John Faller, Commission Chairman Walter A. Jones,

Chief Engineer Samuel Marshall, Secretary of Highways Roy Brownmiller,

and Commissioner Charles Carpenter.

The engineers also had to change

they way they designed highways. Highways had always been built with

flat curves to discourage speeding. Now, the engineers were expected

to design easy grades, to allow cars and trucks year round use. Long,

sweeping curves would give ample room for high speeds and safe stopping

distances. The engineers decided on the following

standards:

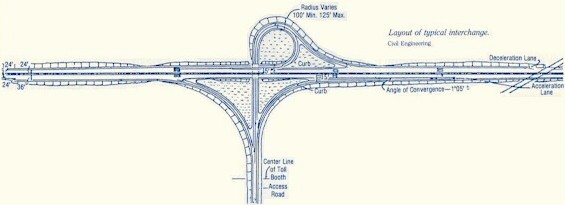

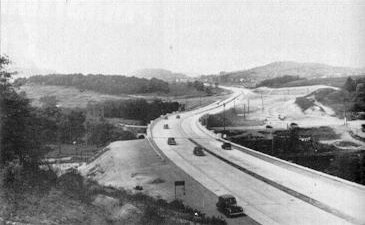

What separated this highway from others was that it was considered one continuous design task from Irwin to Carlisle. Charles Noble, a design engineer for the Commission who later moved on to become chief engineer for the New Jersey Highway Department and the New Jersey Turnpike Authority, described this feat in the July 1940 Civil Engineering magazine, "Unlike the existing highway systems of the United States, in which design standards fluctuate every few miles, depending on the date of construction, the Turnpike will have the same design characteristics throughout its 160-mile length. Every effort has been directed towards securing uniform and consistent operating conditions for the motorist." He also went on to say, "In fact, the design was attacked from the viewpoint of motor-car operation and the human frailty of the driver, rather than from that of the difficulty of the terrain and method of construction This policy of design, based on vehicle operation, is relatively new."

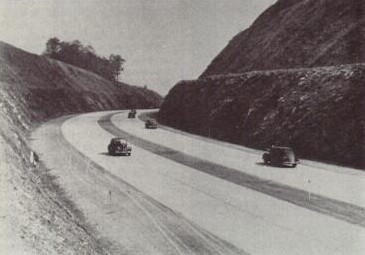

Even with the construction getting underway, there was already a place in the United States where people could experience a long-distance superhighway: General Motor's "Futurama" exhibit at the 1939-40 World's Fair in New York City. Sixteen million visitors took a 16 minute narrated ride through a vision of the United States in the far off year of 1960. Norman Bel Geddes, an industrial designer, built a diorama that had as its focus limited-access superhighways. People were able to get a taste of the things to come. However, many of the principles that were showcased in the exhibit, and used in the Turnpike's design, were already a part of Germany's Autobahns and on a 15-mile section of the Bronx River Parkway in New York City.

As the proposed completion date

drew near, there was one problem the state was facing: no right-of-way

clearing nor excavation had taken place. This doesn't mean that

no work had taken place; however, workers had been busying pumping water

from the abandoned South Pennsylvania Railroad tunnels so that engineers

could determine their condition. That changed when the Commission awarded

Contract Number 1 to the L. M. Hutchinson. After this happened, the

PTC began doing business with owners of 730 properties that lay in the path

of the Turnpike. Houses, farms, and at least one coal mine was acquired

by the state under eminent domain, which Pennsylvania was one of the few

states that then allowed an agency to take land from the holder without coming

to a deal with them, by posting a bond with a court, and agreeing to negotiate

a settlement later. Without this power, the project could not have

been finished as soon as it was.

With all of the preliminary work such as surveying and land acquisition completed, it was time to get down to business. Workers began to pour into the southern tier of Pennsylvania, almost 54 years after they did the same thing for the construction of Vanderbilt's railroad. One of the contractors held the distinction of working on both projects, and one man was documented as having worked on both the South Pennsylvania and Pennsylvania Turnpike projects.

Initially, a headquarters for the project staff was set up at the Department of Highway's district office in Hollidaysburg, then field offices in Shippensburg, Everett, Somerset, and Mount Pleasant.

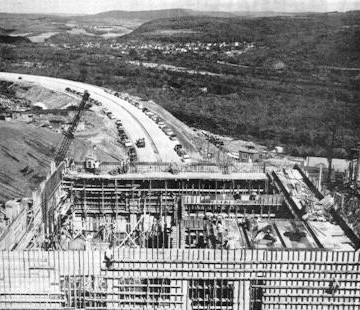

By July 1939, the highway, seven tunnels, and more than 300 structures were under contract, and a month later construction was underway. The contracts were awarded to 155 companies from 18 states. The date that will go down in history as when concrete was first poured on a superhighway project is August 31, 1939. By the spring of 1940, 15,000 workers were helping to shape the future of highway construction. With all of these people coming en masse, housing was placed at a minimal in rural southwestern and south central Pennsylvania. It was so scarce that some employees lived, with their families, in tents near the construction sites. The hourly wages for the workers ranged from 52.5 cents for unskilled laborers to $1.40 for heavy equipment operators, compared to Vanderbilt's pay of $1.25 back in the 1880s.

With the work being hurried along at a fast pace to keep within the timetable, contractors had to work day and night with an average of two shifts a day and sometimes three. Portable generators supplied electricity for the work areas in the remote Pennsylvania woodlands, because little commercial electricity was available. Resident engineers and inspectors manned each site around the clock to insure that the work was able to progress. Approximately $30 million worth of then modern highway building equipment was utilized.

Typical interchange layout (Civil Engineering)

The project called

for:

Crew of the L.M. Hutchison Company, the first contractor on the Turnpike.

(Pennsylvania State Archives)

The completion of the tunnels was the most daunting task of the project. None of the existing South Pennsylvania tunnels that were going to be used for the Turnpike were "holed-through" in 1885; however, they were excavated from both ends. The uncompleted sections ranged from 551 feet in the Kittatinny Mountain Tunnel to 3,379 feet in the Sideling Hill Tunnel. Problems also occurred due to the way that they were initially bored. The railroad's intent was to build double-track tunnels for its double-track line, but as corporate commitments and cash began to slow to a trickle, the design changed so that the tunnels would be only single-track width. Therefore, Turnpike engineers found wide entrances but narrow widths in the deepest parts. However, by utilizing the South Pennsylvania tunnels, a Turnpike engineer of that day estimated that it saved $2 million.

The construction occurred in a round-the-clock cycle, with the contractors working like an assembly-line. One group of workers would would drill about 100 holes 10 feet into rock, and then placed 800 to 1,100 pounds of explosives into the holes. After the detonation, a following shift would clear the rock and rubble. Softer rock required less holes, explosives, and drilling time. Work on the tunnels would average from 11.3 feet to 35.7 feet depending on the type of rock. In addition to widening the tunnels to a width of 23 feet, and a height of 14 feet, the contractors reinforced the walls and floors with concrete lining, and constructed buildings housing the ventilating fans which would blow fresh air into the tunnels and keep carbon monoxide levels safe for motorists. Many of the workers excavating the tunnels where coal miners idled due to a strike against the coal companies by labor leader John L. Lewis.

A problem developed in the Kittatinny Tunnel when workers struck a watery seam of sand, which released 500 to 1,000 cubic yards of red, green, and black sand into the tunnel. It not only required a massive cleanup and resulted in a delay, but also a redesign of the tunnel walls for that section. One accident occurred in the building of the tunnels, when at the Laurel Hill Tunnel site, four men died in a cave-in.

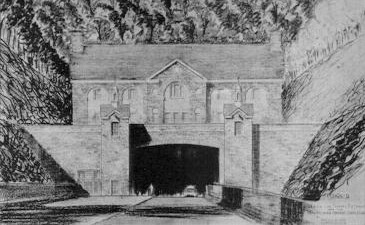

Early proposal for the tunnel entrances.

(Pennsylvania State Archives)

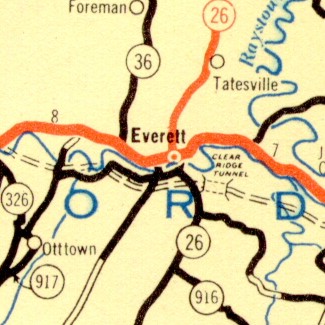

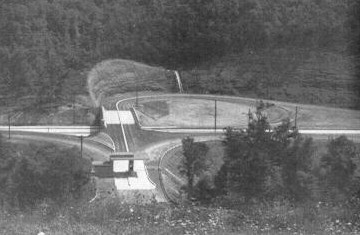

Another massive earth moving operation occurred just east of Everett at a hillside called Clear Ridge, where a tunnel was considered, but instead a large cut was employed. The cut carved is 153-feet-deep and a one-half-mile-long, and at the time, no highway cut that deep had ever been attempted in the United States. Promoters of the highway were quick to name the cut "Little Panama" to trade on the fame of the famous canal built in 1914. One difference between the two was the amount of dirt removed: only 1.1 million cubic yards at Clear Ridge compared to the 200 million cubic yards during the canal construction. The ridge is now known as either the Clear Ridge Cut or the N. R. Corbisello, the contractor from Binghamton, New York whose company performed the construction.

To smooth out the alignment where the terrain was uneven, fill was added and each time compacted to avoid any shifting that could occur when the concrete was poured. Approximately 13 miles of highway was poured in 1939, but wet weather hampered work in spring 1940. By May 8, 1940, only 30 miles of highway had been laid; however, soon 50 paving units would be producing two to three and one-half miles of highway a day.

|

|

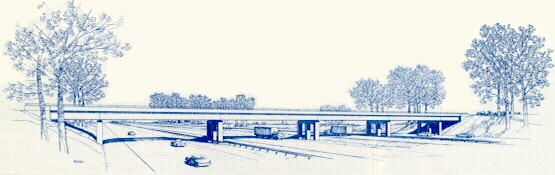

Construction on the bridges and culverts would be a daunting task. 307 of them were designed and built, ranging in the the neighborhood of six feet to 600 feet in length. Twenty-one early overpasses were built with two spans that rested on a support column in the median strip, but federal officials balked at that plan saying it would pose a potential collision hazard. This resulted in most local highways passing over the Turnpike on single-span bridges, many with a gently arched concrete design. Three of the bridges won design awards: the largest bridge, a concrete viaduct east of New Stanton, the Dunnings Creek bridge near Bedford, and the Fort Littleton Interchange overpass. Also, a channel of the Juniata River was altered as part of the project.

Single-span bridge over Turnpike near Donegal.

(Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission)

As spring turned into summer, the pieces of the puzzle were starting to fit. While the remainder of the work was drawing to a close, officials made test drives over the new highway sometimes at speeds of 100 MPH or more. Local motorists sneaked onto the Turnpike for their own personal test drive, a practice that was partially discouraged. Other preparations were underway such as law enforcement of the Turnpike. The Commission wanted its own force; however, Attorney General Claude T. Reno ruled that the then Pennsylvania Motor Police held jurisdiction. With that decision, a corp of 59 troopers was organized and trained at the state police academy at Hershey to specifically patrol the highway, with the cost of enforcement being paid from toll revenue. This branch is now known as Troop T.

With all the excitement building to the opening of America's first superhighway, one organization who would benefit from the opening was voicing concern over the toll rates. The Pennsylvania Motor Truck Association and its national affiliate the American Trucking Associations, negotiated with PTC officials on reducing round-trip fares for trucks, such as those offered to motorists, and reduced rates for high-volume users. The same this was going on, its newsletter Penntrux was carrying ads from Turnpike contractors seeking services such as leasing 45 dump trucks for paving jobs and trucks to haul Westinghouse transformers from rail sidings to the tunnels. Still, PMTA officials were pressing for rates to be cut in time for the highway's ribbon cutting.

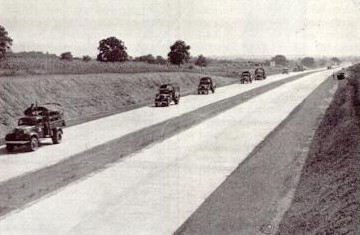

A Fourth of July opening was scheduled, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt was reported to be the one who would cut the ribbon. However, Independence Day came and went with no opening ceremonies, postponed due to weather. On August 6, 1940, an impressive military convoy comprised of the National Guard's 108th Field Artillery battalion, made a 135 mile trip from Indiantown Gap military reservation north of Harrisburg to Bedford utilizing 85 miles of the still-incomplete Turnpike. The training exercise to prevent the "capture" of a theoretically "under siege" Bedford took eight hours and 15 minutes. This was partially from equipment breakdowns and partially from an eight mile detour around the Blue and Kittatinny Mountain Tunnels due to work still going on in that area.

National Guard maneuvers over the Turnpike on

August 6, 1940. (Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission)

Later in the month of August, Walter Jones, commissioner of the PTC, organized a two-day motorcade for 175 guests, including US congressmen and senators from as far away as California. The tour began in Harrisburg on August 25 and the caravan began heading westward at 10:30 AM the next morning. The group stopped along the way to inspect toll booths, tunnels, ventilation fans, the Clear Ridge Cut, and for lunch at 1 PM at the Midway service plaza, while the Bedford Springs Orchestra performed. Jones, unable to attend due to illness, telephoned the group from Washington when its members arrived in Pittsburgh for a banquet at the Duquesne Club.

With no dedication still decided upon, bondholders began getting anxious. Many of them started to point out that each day the highway was not in operation, was another day its debt would not be closer to retirement. At least a half dozen dedication dates had been proposed and eventually scrapped. Some newspapers began to suspect politics were at fault since 1940 was a presidential election year. Whether it was partisan politics at force or not, it was true that scores of public officials of both parties rallied against Roosevelt's controversial campaign for a third term.

Of all of the work taking place in the days leading up to the opening, one thing still had not been worked out: toll rates. On September 11, the Commission approved the first fare schedule which was approximately $.01/mile for automobiles, or $1.50 for the 160 mile trip from end to end, and $2.50 round-trip. Tolls for trucks were based on weight and vehicle class, which was the result of the toll collector's inspection of tire size, ranging from $3 to $10. PMTA unhappy with the toll rates, urged its members to boycott the Turnpike.

The commissioners gathered again, with Jones in attendance, on Monday, September 30. It was that afternoon that he announced that the Turnpike would open for business at a minute past midnight Tuesday morning. With no ribbon-cutting, no ceremony, and no Roosevelt, the highway of tomorrow would be here today.

Fort Littleton Interchange before its opening.

(Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission)

Even though Walter Jones gave less than 12 hours notice that America's first superhighway would open, word began to spread quickly. The news of the grand opening spread from radio station reports that were broadcast throughout the afternoon, and by 6 PM motorists began lining up at toll booths to become the first or one of the first to travel the futuristic highway.

As soon as word got out, travelers and truckers alike altered their plans, with some making special trips from as far away as New York and West Virginia to ride the Turnpike. A family drove 150 miles out of their way, and still managed to get fourth place in line at the western terminus in Irwin. While all the excitement of the opening was going on, the first 50 attendants got prepared to do their job. Later Lee Rishel, superintendent of fare collection, recalled that the order for their uniforms hadn't arrived in time for the opening. So the only official looking clothing they wore was a uniform hat.

Motorists line up at Irwin, waiting for midnight.

(Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission)

Even before the official word came down, it had been speculated that the opening was nearing. A watchman at the Carlisle Interchange had to turn away some 600 motorists from 6 AM to 2 PM on September 30, the day the official announcement was made. Reports circulated about what people were doing to become the first on the highway. One man had waited four days at the Somerset Interchange, a Philadelphia-bound trucker since Sunday morning, and a ballet troupe from Boston heading to Oklahoma had been waiting at the New Stanton Interchange since early that Monday morning.

As the hours up to the grand opening lingered, some motorists slept to pass the time. A couple from Virginia had claimed first in line at Irwin, but after five hours had passed, decided to leave to get something to eat. When they came back, they found two cars had taken first and second place. In the final hours leading up to midnight, motorists at Irwin and New Stanton tried to buy tickets early, but were denied by the good-natured attendants.

As midnight drew nearer, the excitement of the crowds that had gathered at each entrance became heightened. The night added to the drama of the opening, with the shiny blue toll booths gleaming in the light from floodlights, which made a reporter from the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph comment that they were "lighted like the entrance to a beautiful exposition."

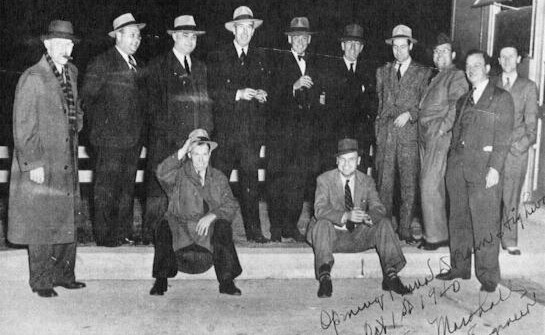

Turnpike's chief engineer, fifth from right, autographed this photo:

"Opening Pennsylvania Dream Highway, Oct. 1st, 1940,

Sam Marshall, Chief Engineer." (Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission)

Finally, the moment people were waiting for had finally come.

Attendants waved the lines of vehicles forward, began stamping, and handing out the first yellow toll tickets. However, before the motorists could head down into the history books, local officials congratulated them and reporters interviewed them. The scene at the western terminus in Irwin resembled a New Year's celebration with drivers honking their horns and cheering.

Spectators and well-wishers upon the opening

at the Irwin Interchange.

(Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission)

At the other end of the highway, where more than 100 people and 40 vehicles had gathered, the scene was the same. The Harrisburg Telegraph captured the event: "At midnight, two black cats ambled across the gleaming cement. A minute later, a ticket-seller dropped his arm in the gesture of an automobile race-starter, and traffic was under way." The first traveler to pass through the Carlisle booths was Homer D. Romberger, a feed and tallow dealer from Carlisle, who traveled 47 miles to Fort Littleton. Mr. Romberger happened to be one of the many who came to the ground breaking ceremonies on the Eberly farm just 23 months earlier. He was handed a ticket by R. H. Pastorius of Hummelstown, one of four on duty. Other Turnpike firsts occurred at Carlisle: the first out-of-state traveler, Bruce Carroll, on a journey back to his home in Ohio, the the first commercial vehicle on an interstate journey bound for Steubenville, Ohio, and the first heavy truck loaded with potatoes (symbolic of Pennsylvania's agricultural heritage) all entered at that toll plaza. In total, 20 cars and four trucks passed thru the plaza at Carlisle in the first hour of operation.

Back at the Irwin Interchange, the first driver to pass through the Irwin toll plaza was Carl A. Boe of McKeesport. He received his ticket from Morris Neilberg of Pittsburgh, one of three attendants on duty. Just after getting his toll ticket, he was waived down by two men from Greensburg: Frank Lorey and Dick Gangle. They were aiming to be, and were, the first hitchhikers on the Turnpike; a practice later banned by law. A father from Pittsburgh with his school-aged son and daughter, Michael and Mary Costello, made an overnight round-trip for the fun of it. Their father said as they waited in line at Irwin, "We filled the tank with gas and the car full of sandwiches. I promised to have the kids back in time for school tomorrow."

With the excitement dying down, the crowds going home, and the night lingering, the first drivers on each end began reaching the opposite side of the Turnpike. When they finally reached the other side, they told stories of traveling 80 and sometimes 90 MPH, while not having to worry about cross-traffic.

Speaking of the high speeds being achieved on the new Turnpike, it happened to be a distinctive feature that there was no set speed limit. In July 1940, a test car managed to do 102 MPH and then Governor Arthur James agreed that the normal statewide limit of 50 MPH would not apply. However, the attorney general convinced the governor that it would be in the best interest of the state if there was a speed limit on the Turnpike, and a week before the highway opened, it was announced that a 50 MPH limit would be imposed. The decree was flatly ignored by both motorists and the troopers patrolling the highway. People entering the highway who asked the attendants what the limit was, their response was simply "Drive carefully." It soon became apparent that the only limitations were nerve and common sense. An Ohio trucker who expected to get a speeding ticket told this story: "I was going down one of those grades at 70 to 80 miles an hour. I looked in the mirror and saw a white car following me. I didn't know whether I was going to get arrested, so I pulled off the road as though to take a rest. The white car pulled off, too. An officer got out and asked me, 'How do you like the road?' I said, 'It's very nice - I guess I get a ticket.' The cop told me, 'No, we aren't interested in the speed limit. As long as you stay on your own side and watch yourself, we won't bother you.'" If only that kind of attitude still prevailed.

One motorist who arrived in the early morning at the Carlisle toll plaza, reported that he traveled the entire 160 miles in two hours and ten minutes, an average of 74 MPH. Others who took longer, from anywhere between 2 hours 30 minutes to 2 hours 40 minutes, still managed to beat the usual time to travel between Harrisburg and Pittsburgh of five and one-half hours via the two-lane Lincoln (US 30) or William Penn (US 22) Highways. It turned out that the new toll highway was not only a faster and easier ride that these two highways, but also shorter: by about five miles compared to US 30 and about 18 miles compared to US 22. A driver managed to cover the 78 and one-half miles from Bedford to Carlisle in only 52 minutes, with an average speed of 91 MPH.

Traveling the highway at high speeds wasn't the only time saving way to accomplish the distance, but even at moderate speeds the highway would still save time. One trucker commented that he was able to cover in four hours what it normally would take ten, saving six hours and 20 gallons of gasoline. With all the time savings being discussed, there was still one complaint with the Turnpike: it didn't go on to Pittsburgh. Merle Foust, who was traveling from Somerset to Irwin, said, "It just ends where it should be starting."

Some travelers got so excited about the experience to driving the Turnpike, that they forgot to keep an eye on the fuel gauge. An attendant at the Carlisle (now Plainfield) Service Plaza reported that four cars had run out of gas, and he helped one of the drivers to push his car to the pumps. And some travelers did not want to partake of the the joy of driving the highway. A motorist from New York threatened to sue the PTC over the dime fare he was charged when he unwittingly entered the Turnpike. He got on at the Middlesex ramps and tried to make a U-turn two miles later at the Carlisle toll plaza. Even though he protested that the highway was not sufficiently signed, a state trooper ordered him to pay the dime toll and leave via the Carlisle ramp. On the topic of out of state travelers, it was noted that about half of the vehicles using the Turnpike on the first day of operation were from outside of Pennsylvania. And from those, about half of the states in the country were represented.

As the first day of operation came to an end, it was reported that 1,550 vehicles had entered the Turnpike at Irwin, and more than 1,900 at Carlisle. The log at the Bedford headquarters of the Pennsylvania Motor Police Turnpike Division noted: "No accidents, no arrests, and no unpleasantness."

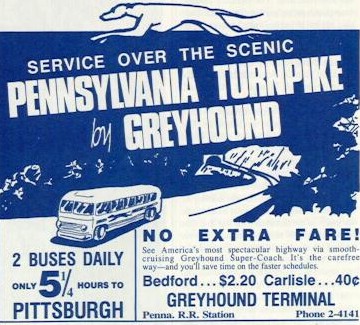

Soon after the opening, Pennsylvania Greyhound Lines reported that it would begin long-haul intercity bus routes over the new highway. Prior to the Turnpike, it would take close to 9 hours to travel between Harrisburg and Pittsburgh utilizing US 22. Now the company was offering twice a day service taking only five and one-quarter hours which included a rest stop at Bedford. The Motor Bus Society reports that Greyhound was the first commercial account for the Turnpike. The Public Utility Commission, the agency responsible for regulating railroad and highway transportation commerce, granted the company intrastate rights to use the Turnpike with stops at Bedford and Somerset. The provision is that this new service did not have a negative impact on its existing routes. Somerset Bus Company was also granted rights to utilize the Turnpike for service between Somerset, Irwin, and Pittsburgh with stops at Donegal and New Stanton.

Advertisements like this began to appear in

the Harrisburg newspapers.

(State Library of Pennsylvania)

Still protesting the truck toll rates, the Pennsylvania Motor Truck Association (PMTA) continued to urge its members to boycott the new Turnpike while they kept negotiating for a reduction. They pleaded with the PTC that many operators could not afford the rates. However, the advantages in delivery time, fuel savings, and driver comfort proved to be a more attractive point and within weeks, interstate and intrastate trucks without regulatory limitations became drawn to the Turnpike by the thousands.

| TRAFFIC POINTS OF ENTRANCE AND EXIT There are eleven (11) Interchanges located at selected points along the Turnpike route. These Interchanges have been strategically located so that they offer convenient connections with existing highways. The following diagrams show the eleven (11) points of exit and entrance with a brief description of the traffic flow for each. Each Interchange, as shown, is self-explanatory through the use of directional arrows and appropriate description for each direction of traffic--for entering and leaving the Turnpike. If there are any questions relative to reaching your destination they will be answered by the ticket-office or service station attendant. |

|

|

This interchange makes a direction connection with U. S. Route No. 30 (Lincoln Highway). Traffic to and from the Turnpike for points of destination are shown by the directional arrows. The ticket office at the western terminus is located directly across the Turnpike proper on 6 traffic lanes. All other ticket offices, except at Carlisle Interchange, are located off the Turnpike on spur lanes provided for entrance and exit. (MILE 0) |

|

This Interchange, being located on the heavily traveled U. S. No. 119, will serve to expedite traffic east and west across Pennsylvania from southwest to the east and vice-versa. Note ticket office is off the Turnpike proper. Follow directional arrows for correct guidance. (MILE 8) |

| New Stanton Gas Station

(W-B) MILE 11 |

|

|

This Interchange being located in a mountainous region and in the heart of a vacation-land serves as a direct connection to the nationally known town of Ligonier twelve miles north of this point. The annual Rolling Rock Horse Show is held in this community. (MILE 24) |

| Laurel Hill Tunnel--4,541

feet MILE 33 |

|

| Laurel Hill Gas Station

(E-B) MILE 36 |

|

|

Somerset Interchange is located north and adjacent to the town and will serve as a direct connection to north-south traffic traveling on U. S. Route No. 219. Directional arrows point out destinations and mileage from this Interchange. (MILE 43) |

| Somerset Gas Station

(W-B) MILE 45 |

|

| Allegheny Tunnel--6,070

feet MILE 56 |

|

| New Baltimore Gas Station

(E-B) MILE 63 |

|

|

The Interchange is located at the mid-point between Harrisburg and Pittsburgh. It makes a direct connection to the heavily traveled U. S. Route No. 220 for north-south traffic and is only two miles north of the nationally known resort town of Bedford. (Considerable traffic will flow from the south through Bedford to this Interchange for east-west destinations.) (MILE 79) |

| Midway Gas Station

(E-B/W-B) MILE 80 |

|

|

The Interchange is conveniently located with a direct connection to the Lincoln Highway--U. S. Route No. 30. It will absorb and discharge a considerable volume of traffic using Pa. Route No. 126, which leads directly south into Maryland and Virginia, as well as from the normal flow of traffic on the Lincoln Highway proper. (MILE 96) |

| Rays Hill Tunnel--3,532

feet MILE 98 |

|

| Sideling Hill Tunnel--6,782

feet MILE 103 |

|

| Cove Valley Gas Station

(W-B) MILE 105 |

|

|

The above traffic facility located near Ft. Littleton on U. S. Route No. 522 will serve a north-south influx of traffic desiring direct connections with east-west destinations. It is anticipated that considerable hauling of coal from the famous Broad Top Coal Fields will use this Interchange for east-west distribution. (MILE 115) |

| Tuscarora Mountain Tunnel--5,326.5

feet MILE 120 |

|

| Path Valley Gas Station

(E-B) MILE 121 |

|

|

The Willow Hill Interchange is provided to serve several connecting valleys throughout this area, which, during various seasons of the year receives a great amount of tourist travel on Pennsylvania Route No. 75. (MILE 124) |

| Kittatinny Mountain Tunnel--4,727

feet MILE 131 |

|

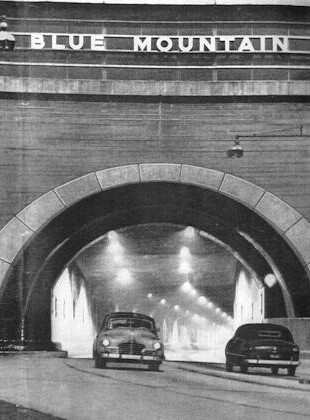

| Blue Mountain Tunnel--4,339

feet MILE 132 |

|

|

Blue Mountain Interchange is located two miles east of the Blue Mountain tunnel, making a direct connection with Pennsylvania Route No. 944, for points south by way of the Shenandoah Valley, and traffic from other routes such as the Lincoln Highway passing through Chambersburg, which is only fourteen miles south of this Interchange. (MILE 134) |

| Blue Mountain Gas Station

(W-B) MILE 136 |

|

| Carlisle Gas Station

(E-B) MILE 152 |

|

|

This Interchange is located north and adjacent to the historic town of Carlisle which in reality is the gateway to the west for traffic from all points east, as shown above. The 4-lane ticket office is located directly across the Turnpike proper, as is the ticket office at Irwin. Traffic desiring to proceed westward from this Interchange will follow the directional arrows as noted. (MILE 157) |

|

The present eastern terminus of the Pennsylvania Turnpike is located at Middlesex, just two miles beyond the Carlisle Interchange, making a direct connection with U. S. Route No. 11 for points north and east, as shown. No ticket booth was provided for this Interchange due to its close proximity to Carlisle. When the Turnpike is extended to Philadelphia this Interchange may be eliminated. The foresight and discretion show by the Commission in its planning will prove economical. (MILE 160) |

|

†All

distances to tunnels are given to middle of each tunnel. |

|

The weekend of October 5 and 6 was the first chance many people got to traverse this gem of a highway for the first time. Even though the day turned out to be pleasant in terms of the weather, it would not be as pleasant for the Turnpike Commission. The amount of traffic in the morning was light, but by afternoon the numbers grew with after-church and after-Sunday dinner motorists flocking to the interchanges and throwing them into pandemonium. Three of the interchanges ran out of passenger-car toll tickets and had to resort to giving light truck tickets or hand-written notes.

Hexagonal toll booths on the original Turnpike.

(Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission)

The largest problem that occurred wasn't trying to get traffic onto the highway, but trying to get the traffic off the Turnpike. Traffic would back up for miles at all of the interchanges waiting to get off, as the time to collect the ticket and toll and giving change when needed took longer than handing a motorist a ticket. The attendants were so busy that they couldn't even break for lunch, and some were seen eating a sandwich with one hand while handing out tickets with the other. Employees of the PTC expecting to go out for a cruise with their families were pressed into service directing traffic at the Carlisle Interchange. The jams were so bad that all 59 Pennsylvania Motor Police officers assigned to the Turnpike were on duty trying to ease the back-ups. A traveler from Johnstown said he waited four hours and 50 minutes in line to leave at Somerset. Back-ups at Bedford and Carlisle totaled six and three miles respectively. The tunnels also saw the same amount of congestion as two lanes went into one to go through them. However, the PTC not only did a booming business in terms of toll revenue, but also from sales at the Standard stations with 50,000 gallons sold that day.

The Bedford Gazette observed that many travelers did not intend to travel the entire length of the highway, but rather a small portion was the cause for the traffic jams. Many people entered at Irwin and planned to exit at Somerset, with their return trip back over the Turnpike. However, when the approached the interchange and witnessed the hundreds of cars backed-up, decided to continue on to Bedford. Then arrived there to find the jam up even worse than the one at Somerset. According to the Harrisburg Evening News, Carlisle Pike (US 11) was "black with automobiles traveling to and from the turnpike." Harrisburg police had to work a double shift to handle the traffic in the downtown that spilled over from the Turnpike. The jams began to ease between 10:30 PM and midnight, with early estimates ranging from 10,000 to 12,000 vehicles. However, when the tickets were finally counted, the total came to 27,000 with only one minor accident reported.

Curved viaduct east of New Stanton.

(Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission)

After the hectic weekend had passed, Governor Arthur James became the first celebrity to take a ride down the Turnpike on October 8. He was returning to Harrisburg after visiting an ill friend at the Mayo Clinic. The Governor flew to Chicago where he took a Pennsylvania Railroad train to Pittsburgh, then he drove to the capital at 50 MPH which he himself decreed the maximum to be on the highway just weeks earlier. Four hours later he arrived at the Carlisle toll plaza and declared the Turnpike to be "a peach of a road." He also commented on what is now called "highway hypnosis" by saying he had "the most somnolent trip I've ever taken" and suggested that "(t)hey ought to give everybody a cup of coffee before they go onto the Turnpike to keep them awake." For those wondering, his toll was waived: "They told me I'm the only man privileged to sign my name."

At the same time the governor was doing his own test drive, the Commission was gearing up for the coming weekend. Workers added temporary toll booths and asphalt lanes at all of the interchanges except Irwin's, and more toll tickets were printed. Its a good thing too, because on the second Sunday of operation, 30,000 vehicles passed through the toll plazas but without the congestion of the previous weekend. There was some trouble getting from the booths onto the state highways and into the towns near the interchanges. In the end, the towns came out on top with motels, tourist homes, and restaurants packed with travelers. The same business that worried the Turnpike would take business off of US 30. Some motorists still did not understand the expressway concept. One drove the wrong way on an exit ramp at Middlesex and wound up in a minor accident, and another pulled up to the Carlisle toll plaza asking how to get onto the Turnpike.

The Turnpike officials released the figures showing that in just four days of operation, the highway had carried 24,000 vehicles or about 6,000 a day. That was nearly double the number that was forecasted but the Turnpike's own traffic planners. With the weekend numbers of tourists and sightseers added to that, the number jumped to 150,000 for the first 15 days of operation, or about 10,000 per day. Many of these trips were one-time curiosity trips, and were unlikely to mirror any trend in a normal day of operation.

The number defied the dire predictions that the US Bureau of Public Roads, predecessor to the Federal Highway Administration, gave of 715 cars a day. Their position was not only anti-toll highway but also against intercity limited access highways, either toll or free. At the same time Pennsylvania was building their highway, President Franklin Roosevelt asked the Bureau's director, Thomas H. MacDonald, to conduct a study into building six national toll highways: three east-west and three north-south. MacDonald believed that toll highways would never attract enough customers to repay their construction costs, and instead backed the improvement of urban highways as more important. However, he did agree that a national system of highways was useful, but only ones with two lanes would be needed for much of the distance. This at a time when the total distance of four-lane highways measured 11,000 miles, among the three million miles of highways in existence in the United States. The results of the study were in a report to Congress titled Toll Roads and Free Roads. In Bruce E. Seely's 1987 book titled Building the American Highway, he noted that the Bureau's report "attacked a national system of toll superhighways as wasteful, presenting traffic estimates that showed that only 3,346 of the proposed 14,336 miles required more than two lanes. Only 547 miles, it predicted, would return more than 70 percent of the receipts needed to retire the construction bonds, and only the 172 miles from Philadelphia to New Haven (Conn.) might break even. BPR analysts assumed that public resistance to tolls would deter traffic and that limited access would prevent superhighways from serving the local traffic that formed the majority of all trips, even if motorists wished to use them. The BPR simply believed toll highways were unprofitable."

The study separated the six toll highways into 75 segments and estimated that the portion comprised of the Turnpike would rank no higher than 19th in traffic volume. The majority of cars owned at the time belonged to families with an income of no more than $1,500/year. The report said, "The cost of gasoline consumed on a trip may amount to a little more than a cent a mile. To the motorcar owner with an income of less than $1,500 a year, a toll of one cent per mile is likely to appear as a 100 percent increase in his cost of operation. He would view this as an additional cost that he is not likely to pay."

Of course, the traffic counts produced by the Turnpike that confounded the critics, is what Phil Patton cited in his 1986 book Open Road. "The BPR had no notion that the construction of new superhighways, like the introduction of such inventions as the telephone and the auto itself, might create its own demand."

One of the effects of the Turnpike's success was how it altered the course of national highway policymaking. MacDonald's thinking was based more on the transportation needs of 1930s America, before two factors of long distance motoring that would grow in the post-war United States: rise of the trucking industry, and recreational travel. In the end, MacDonald was so wrong about toll highways that his agency lost clout in setting the federal government's highway agenda, and marked a historic turning point. From that time on, the decisions would be made increasingly by officials sensitive to the voters, rather than just the engineers. With the vigor of the Turnpike's success on their side, Roosevelt and Congress went back to the drawing board with the information contained in Toll Roads and Free Roads. This would eventually become the blueprint for today's Interstate Highway System.

The impact of a superhighway available to carry goods safely was felt by a 19-year-old Bill Yocum. He was a truck driver who hauled Chrysler automobiles from Detroit to the port at Buffalo to Washington, DC. K.U.K. Auto Transit of Williamsport, the company he worked for, avoided operating over the shorter but mountainous US 30, and preferred to use US 6 through the northern tier of Pennsylvania, then down the Susquehanna River valley to Harrisburg. US 22 was not considered a statewide trucking corridor because of a low-clearance underpass in Huntingdon. When the Turnpike opened, the company began using it and Yocum got to experience the highway's first winter first hand. "I can remember sitting in one of the Turnpike restaurants with other drivers on a snowy night, and our conversation was about the fact that we wouldn't be out driving at all if it weren't for the Turnpike. These winter nights when ordinarily truckers would simply have to tie up." Yocum would later become president of the Pennsylvania Motor Truck Association (PMTA), commented that the highway cut a full day off the round-trip journey between Detroit and Washington.

Winter maintenance in the early days.

(Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission)

He also commented on when trucks carrying flammable or explosive cargo were allowed to travel through the tunnels, after traffic was stopped in both directions. The practice was stopped less than a year after the highway opened, whether due to traffic disruption or because of the hazard. Ever since then, those types of cargo have been prohibited from using the tunnels.

It wasn't only the truckers who were impressed, but also the motoring public. One of them on October 31, 1940, wrote on a Turnpike postcard mailed from Camp Hill to Pittsburgh: "We came through the tunnels. The lights make them like a fairy land." Even a Ford Motor Company publication exalted the highway as "the closest the average American comes to breaching the sonic barrier is when he eases himself behind the wheel of the family car (no doubt implying a Ford) and has a go at the Pennsylvania Turnpike."

|

|

At the end of 1940, the traffic totals looked like this: 514,231 cars, 48,170 trucks, and 2,409 buses. From these users, the total revenues equaled $562,464, but it didn't mean that these drivers had adjusted to the skills needed for high-speed, quick reaction situations. It definitely did not compensate for the fact that cars of the time were not built to go 80 MPH, or even 60 MPH for that matter. Magazines at the time reflected this in stories they did about the Turnpike. Fortune noted: "The Turnpike is the first American highway that is better than the American car. As such, it will represent the maximum in road construction for many years. It is proof against every road hazard except a fool and his car." Engineering News-Record noted this: "Excessive speed on the Pennsylvania Turnpike has been checked more by the experience...that cars and tires do not stand up under high sustained speed...than by any other means." Tire blowouts and engines overheating were common along the highway. It was not speed or a tire blowout, but icy conditions that led to the first fatality on the Turnpike when Arthur B. Turner, 66, of Bethlehem lost control of his car and struck a center bridge pier one and one-half miles west of Donegal. He was pronounced of dead of a skull fracture after being admitted to Westmoreland Hospital in Greensburg.

The year of 1941 brought about a resolution between the PTC and the Pennsylvania Motor Truck Association over the toll rates for trucks. A plan for reduced tolls was agreed upon, which meant that carriers that were volume users would get a discount of as high as 20%, and monthly fleet billings were also made available.

April 15, now known as income tax day, was instead a welcome day in the year 1941. On that day, Governor James signed Act 10 which implemented a 70 MPH speed limit for personal automobiles, and a truck speed limit that varied between 50 and 65 depending on the size and weight. The only decrease in the speed limit along the Turnpike was at the tunnels, when it dropped to 35 MPH.

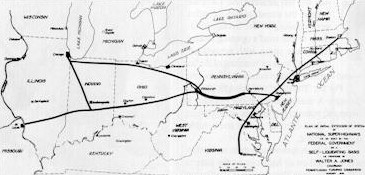

Clear Ridge Cut

(Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission)

With the Turnpike level of service well established, the media and public both looked toward the benefit of extending the comforts of superhighway travel east to west and north to south. Even before the first car tires made contact with the Turnpike, Chairman Jones his own proposal for a 1,800-mile, $860 million system of toll expressways from Richmond, Virginia to Boston; Philadelphia to St. Louis (incorporating the Turnpike); Pittsburgh to Chicago and Indianapolis to Chicago which looked similar to the Pennsylvania Railroad system map. Jones wrote of this vision, "However advantageous, it is hardly possible that any of the states will be able to contribute much to the development of a national system of super-highways...our task is a national one and the understanding of this need must be brought to the attention of Congress in a convincing manner. A little under two decades later, the Interstate Highway Act would use this information to establish a 90%/10% federal-state cost-sharing formula.

Although he had planned an expansion to points outside of the Commonwealth, the most important extension planning would be for intrastate highways. Four months before the Turnpike opened for business, Governor James signed Act 11 which authorized a extension eastward to Philadelphia. In an message to the state legislature on January 7, 1941, Governor James asked the law makers to get federal approval to "extend Skyline Drive from Front Royal, Va., along the crest of the Pennsylvania mountains, to the Delaware Water Gap...and second, that the federal government give consideration to a new superhighway for Pennsylvania to extend from our ocean port at Philadelphia to our lake port at Erie." With the Turnpike open for less than a year, on June 11, 1944 he signed Act 54 which authorized the Western Extension.

This was based more on the performance

of the highway so far. In the first 12 months of operation, 2.4 million

vehicles, nearly twice the projection of 1.3 million, passed through toll

plazas up and down the system. However, this volume would start to

trail off as the United States was pulled into World War

II.

From the day when the Turnpike welcomed its first customers, the thoughts in the back of people's minds were of what was occurring across the Atlantic. Reports of Britain's five hour bombing of Berlin and Germany's latest bombing of London shared the front page with the highway's opening. With the specter of war looming over the US, changes came swiftly to the Turnpike. The number of troop and material movements increased, while the number of civilian trips decreased.

Military convoy on the Turnpike.

(Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission)

The Federal Office of Defense Transportation imposed a 35 MPH speed limit on all highways beginning in December 1941, with war supply movements exempted. Gasoline and tire rationing began in March 1942. It didn't take long after those two major impediments to travel to show up in toll receipts. Use of the Turnpike fell a whopping 70% from 2.1 million in 1941 to just 581,000 in 1943.

The number of trucks on the highway increased from 48,000 in 1940 to about 300,000 in 1942, and remained consistent through the war. Not only did revenue drop, resulting in the PTC dipping into financial reserves to pay the bond obligations, but also the number of troopers patrolling the highway. Some went off to war and other were not required as the level of traffic did not warrant the level of supervision that pre-war traffic did. From the initial 59 troopers that were brought on when the highway opened, the number fell to 48 in 1941, 26 in 1942, 20 in 1943 and 1944. The men who pumped the gas at the service plazas also heard Uncle Sam's call to arms. Just like in every other "home front" duty, women replaced the men at the pumps.

One of the many

women who took over

at the pumps. (PTC)

Even with the decreased number of troopers on the Turnpike, there was one place their numbers increased: the tunnels. With the possibility of sabotage, special details of the motor police were posted at the entrances to inspect any vehicles that appeared to be or whose driver acted suspicious.

Many publications hailed the Turnpike

as a savior to the world during the war. The Highway Builder, the

Pennsylvania construction industry's magazine said, "Should the conflagration

now destroying Europe ever blaze across the Atlantic to sear these shores,

the Pennsylvania Turnpike would ably demonstrate its ability to carry adequately

the heavy gear of war." Another magazine said, "Over the Pennsylvania

Turnpike (costing less than one battleship) a great army could be rushed

eastward from beyond the mountains in the shortest possible time." Seeing

the potential military value of the Turnpike, in 1944, Congress passed a

bill that outlined a national system of limited-access highways which became

a basis for the Interstate highway act that would be passed a decade

later.

When the boys came back from the front, the nation was ready to get back to normal. The Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission was also looking forward to a normal pace, which meant getting ready for the return of civilian use and reviving plans to expand the system. A setback occurred when Walter Jones, the first chairman and architect of a plan for a 1,800-mile-long system of toll expressways that would serve 40% of the nation's population, had fallen ill and resigned in 1942 and then effective on September 1, 1943, his commission seat. Three days later he died. Two other original members, Frank Bebout and Charles T. Carpenter, died earlier. In 1946, Governor Edward S. Martin filled the vacancies, and the new commission picked up from where Jones left off.

Walter Jones' original plan for a 1,800-mile-long

system of Eastern and Midwestern toll highways.

(Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission)

In 1946, the same year tire rationing ended, the highway handled 2.4 million vehicles, which was about the same number that used it in its first year. The same year, the Commission decided to do some financial "housekeeping." The Commission decided to issue new bonds with their financier Fidelity-Philadelphia Trust Company. The new two and one-half percent interest rate would help raise capital to retire the old bonds. There was one problem: this arrangement restricted the use of all revenue to the original Turnpike section.

To get around this stipulation, the PTC set up three separate operating and accounting divisions, each with its own bond issues to get extensions to Philadelphia and Ohio underway. The last piece of the puzzle was to get legislation to approve this, which occurred in 1947 when Governor James H. Duff signed a law that merged the proposed eastern and western extensions and the existing highway into one body. This piece of legislation was known as the Trust Indenture of June 1, 1948. A total of $87 million worth of bonds were sold to help get the Philadelphia Extension going, which was a 100-mile-long section from Middlesex to King of Prussia. Ground breaking ceremonies took place on September 28, 1948 in York County. All this was happening as more people flocked to the original highway. In 1949, before any of the extensions opened, the Turnpike handled 3.8 million vehicles which was three times what the planners envisioned.

Governor James Duff and his wife Jean Taylor

Duff with the first shovel of earth at the ground

breaking for the Philadelphia Extension.

(Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission)

Pennsylvania's success with the toll highway concept influenced other states to follow suit. Maine became the first in 1945, when it authorized a 47-mile-long project paralleling US 1. The other states that followed included Colorado, Florida, Indiana, Kansas, Maryland, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Texas, and West Virginia.

In 1946, the Turnpike was recognized by a competitor: the Pennsylvania Railroad. In a corporate history published for the PRR's centennial, authors George H. Burgess and Miles C. Kennedy told of William Vanderbilt's South Pennsylvania Railroad: "Nearly 100 years later, when the South Penn(sylvania)'s name was almost forgotten...much of the old right of way, with its grading and uncompleted tunnels, would fit into a scheme for a superhighway between Harrisburg and Pittsburgh, so at last events went through the full cycle...now highway vehicles supply the competition for which the South Penn(sylvania) Railroad was designed."

For construction workers building the Philadelphia Extension, the project was not a daunting task. They did not have to endure excavating tunnels through mountains as workers did on the original Turnpike; however, they did have to deal with the Susquehanna River. Engineers designed a 4,526-foot-long bridge, with steel girders resting on concrete piers. The $5 million bridge was supplied and erected by the Bethlehem Steel Corporation, whose Steelton plant is where the eastern end of the bridge passed through. However, only the handrails were fabricated at that plant. In all, 28 contracts were awarded to 17 companies for the construction of the extension, which took two years to build like the original Turnpike. The Philadelphia Extension opened to traffic on November 15, 1950 with the exception of the Gettysburg Pike Interchange which opened on February 1, 1950. To accommodate the extension, the original mainline toll plaza that extended across the highway was demolished and the ramps to Carlisle closed. The Middlesex Interchange was upgraded with a new toll plaza and ramps, and renamed the Carlisle Interchange.

Former eastbound off-ramp to the traffic circle in Carlisle west of PA 34. |

Looking across the traffic circle at the off-ramp. On the right is Cave Hill Road, which was the on/off-ramp to/from the Turnpike. |

With the extension's opening, the eastern terminus of the Turnpike now lay only 15 miles northwest of Philadelphia's central business district. By the end of 1950, even without the contribution of traffic from the new extension, the Turnpike had handled 4.4 million vehicles.

|

|

|

The Western Extension proved to be another challenge for engineers and construction workers alike. The right of way covered more rugged territory than the Philadelphia Extension did, and crossed two major rivers. A 2,180-foot-long bridge was constructed over the Allegheny River at Oakmont, and a 1,540-foot-long bridge over the Beaver River north of Beaver Falls. In order to provide enough right-of-way for the road, the eighth green at the famed Oakmont Country Club, site of numerous US Open golf tournaments, had to be moved. The extension opened in sections: Irwin to Pittsburgh on August 7, 1951; then from Pittsburgh to the Gateway Interchange on December 26, 1951. The only exception was the Beaver Valley Interchange which opened on March 1, 1952. When this section opened to traffic, it dumped torrents of traffic onto Petersburg, Ohio which would last three years until the Ohio Turnpike opened on December 1, 1954.

|

|

Just as the changes at Carlisle were needed for the Philadelphia Extension, the same had to be done at Irwin. However, this time, the original booths were not demolished as the new extension passed to the east of them. Connecting ramps and an overpass were constructed to and from the toll plaza.

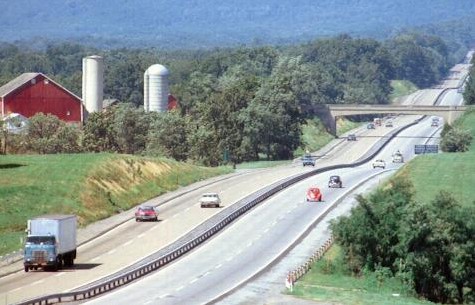

The engineers who designed these two extensions modified the designs that were used for the original Turnpike. Adjustments to the concrete used for the roadway and an additional sub-base was laid for better drainage. Larger service plazas were constructed, and as early as 1946, some of the older plazas were expanded to handle more people and a full meal service instead of just a coffee-shop menu. Pittsburgh based Gulf Oil secured the rights to provide gasoline at the service plazas on both extensions, and as Standard Oil did, subcontracted the restaurant services to Howard Johnson's. The overpasses also changed design from concrete arched bridges to all steel construction on the Western Extension. The design specifications also differed on the extensions: Philadelphia has grades of two percent and curves of three degrees, and the Western has grades of three degrees and curves of four degrees. A far cry from the original's specifications of grades of three percent and a maximum curve of six degrees.

The year's traffic count reflected the growth of traffic using the Turnpike. Even with the Western Extension being open for six days of 1951, the traffic count was 7.4 million with the addition of the Philadelphia Extension. It would not be until both extensions were open for an extended period, stretching 327 miles across the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, that the count would be pushed to 11 million vehicles.

With the completion of the Western Extension, the only logical way to expand was to New Jersey. A 33-mile-long section from the Valley Forge exit to Bristol and a proposed crossing of the Delaware River. With a bridge, travelers could access the New Jersey Turnpike, thus making it possible to travel from New York City to the Ohio line. In May and June of 1951, Governor John S. Fine signed a bill to construct the Delaware River Extension and a joint toll bridge with the New Jersey Turnpike.

Everything seem fine; however, there was a problem. The 1948 indenture under which the Philadelphia and Western Extensions were financed allowed additional expansions. The problem was work could not start on a new extension until the previous project was open to traffic for two years, which would mean waiting until 1954 to begin financing. Governor Fine signed a bill in August of 1951 to move the timetable up, so he signed the Indenture of September 1, 1952. It was a supplement to the bill of 1948 and was intended to be used for future expansion.

To finance the Delaware River Extension, the PTC issued $65 million worth of bonds in September of 1952. The current configuration at the Valley Forge Interchange had to be converted from a terminus to an "off-line" interchange. It was built to connect to a future highway that would connect the Turnpike to Philadelphia: the Schuylkill Expressway.

The 1,224-foot-long bridge over the Schuylkill River was the longest structure on the extension. On August 23, 1954, the Delaware River Extension opened to the Norristown and Willow Grove Interchanges. The remaining interchanges opened as follows: Fort Washington on September 20, Philadelphia on October 27, Delaware Valley on November 17.

While the celebration of the opening was taking place, the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission was not only looking to building the Delaware Bridge but also a spur to Scranton. The proposal of a spur to Scranton was not a new idea, it had been authorized as early as 1947. In 1954, the commission combined the financing of both projects into one $233 million bond.

The ground breakings for both proposals were held on March 25, 1954 for the Northeast Extension and June 22, 1954 for the Delaware River Bridge. The bridge was constructed and jointly financed by the New Jersey Turnpike Authority and the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission. It cost $27,200,000 and opened on May 23, 1956 at 11:30 AM when Governors George M. Leader of Pennsylvania and Robert B. Meyner of New Jersey met in the middle of the span to cut the ribbon. The bridge is 135 feet above the Delaware River because of the ship traffic that utilizes the river. The significance of the bridge is that it would soon be possible to travel between Maine and the Indiana-Ohio border (and soon to Chicago with the completion of the Indiana East-West Toll Road) without encountering a traffic light, cross street, or grade crossing.

The first section of the Northeast Extension opened on November 23, 1955. Its initial 37 miles opened from an interchange east of the Norristown Interchange to the Lehigh Valley Interchange. Interchanges at Lansdale and Quakertown opened later on December 3 and December 10, respectively. From the Lehigh Valley Interchange, another ten miles opened to a temporary interchange at Emerald on December 28, 1955. Work was still taking place to build the two-lane, 4,461-foot-long tunnel through Blue Mountain. It was named Lehigh Tunnel so as not to be confused with the tunnel through the same mountain on the mainline Turnpike. It would been named after commission chairman Thomas J. Evans if he hadn't been convicted of conspiracy to defraud the PTC of $19 million on July 25, 1957.

Construction of the Lehigh Tunnel.

(Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission)

On April 1, 1957, the Northeast Extension was opened to the Wyoming Valley Interchange near Wilkes-Barre. At this time, the temporary interchange at Emerald closed. The last 16 miles to Scranton opened on November 7, 1957. With the opening, it brought the Northeast Extension's total length to 110 miles, and the total system length to 470 miles.

With all the excitement over bond issues and expansion, people forgot about one point. The original planners anticipated that the Turnpike would retire its debt by 1954 and thus be turned over to the state as a free highway. But those pioneers of superhighway planning could not foresee postwar economic inflation, rise in traffic flow, and the need to expand.

Railroad-like signals

indicated the 45 MPH

speed limit on bridges.

(PTC)

The Northeast Extension was not the only branch to be proposed. Many extensions were drawn in the 1940s and 1950s, and even some received legislation. In a 1954 Turnpike brochure was the sentence. "When finally completed, the Pennsylvania Turnpike will consist of more than 750 miles." Some Turnpike maps even had over 1,000 miles as a target length.

Here is a list of the proposed routes the Turnpike Commission

considered:

These plans never came to be as toll expressways. By the time 1954 came around, support for toll highways died down, and on June 29, 1956 President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Interstate Highway Act. This set up the financing for $25 billion in federal funding for a national system of four lane, controlled-access free highways. By offering 90% of the funding, states jumped on the bandwagon and abandoned plans for toll highways.

The 1958 Annual Report stated about the extensions: "In all of the authorized and previously authorized proposed extensions, the Turnpike Commission is empowered to determine the exact routes with the approval of the Governor and the Secretary of Highways, nevertheless construction cannot be started until the project is determined to be feasible and has been financed. The feasibility of any of these extensions will be influenced by the program of the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways." They didn't know that half of it, as eventually these extensions were built; however, not all with the help of the Interstate Act.

TURNPIKE EXTENSIONS PRIOR TO 1956 |

|

Extension Name |

Highway It Became |

Scranton Extension |

|

Philadelphia Loop Extension |

|

Chester Extension |

|

Gettysburg Extension |

|

Northwestern/Southwestern Extension |

|

Northwestern Extension |

|

Sharon to Stroudsburg Lateral Connection |

|

While the Turnpike Commission was

looking towards expansion, two service plazas were closed in 1957. The

Laurel Hill just east of the Laurel Hill Tunnel and New Baltimore both on the

eastbound side of the Turnpike.

As the Turnpike was preparing to count its 200 millionth vehicle, it was apparent that something had to be done to bring the growing traffic count under control. Now that the annual volume was running at 31 million vehicles, 24 times what the planners envisioned, congestion began to grow. The largest contributor to the congestion were the east-west tunnels. Beginning in 1951, eastbound traffic would begin to backup at the Laurel Hill tunnel during summer weekends, and by 1958 it was a common sight anytime between June and November. The jams would stretch as far as five miles back from the mouth of the tunnel waiting to squeeze from two lanes into two, which made PTC officials look toward eliminating these bottlenecks.

A picture illustrating the dangers of the two-lane

tunnels. (Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission)

Not a minute too soon either, as the New York Thruway began to slice into the Turnpike's profit. Built according to the new Interstate standards, it was a far cry from two-lane tunnels and narrow median strip on the Turnpike which PTC officials publicly called obsolete.

If the New York State Thruway wasn't enough competition for the Turnpike, it got some from another highway in its own state. On March 19, 1959, the ground breaking for Interstate 80/Keystone Shortway took place. Originally proposed as the Turnpike's Sharon to Stroudsburg Lateral Connection, the project was handed over to the Department of Highways to be built as part of the Interstate system. Philadelphia city officials, including Mayor Richardson Dilworth, opposed I-80 because it would divert revenue from the Turnpike and freight from the Delaware River's docks to New York City's. This was a kind of revival of the trade rivalry of the 1830s between the two seaports.

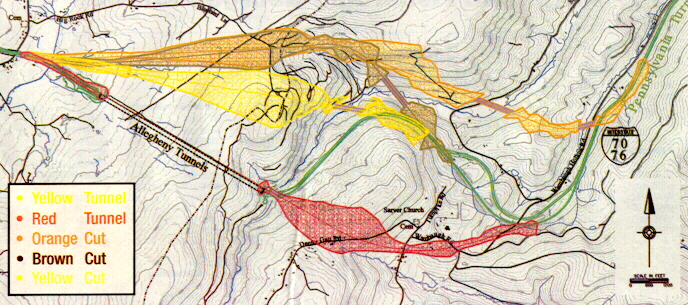

Studies began in the mid-1950s to determine what exactly to do with the tunnels, and the first two studied were the Laurel Hill and Allegheny Mountain Tunnels. It focused on the cost of benefits of building a two-lane parallel tube at both locations, with additional studies conducted for Rays Hill, Sideling Hill, Tuscarora Mountain, Kittatinny Mountain, and Blue Mountain.

The conclusion of the study ushered in a $100 million program that would last at least a decade. The first order of business was to construct a three-mile-long bypass over Laurel Hill and around the tunnel, which would be closed. Construction began on September 6, 1962, and the new alignment complete with a broad median and a truck climbing lane in each direction opened on October 30, 1964. The new section became the highest elevation on the Turnpike system at 2,603 feet, up from the old record of 2,200 feet in the Laurel Hill Tunnel. A 145-foot-deep cut was chiseled out of the mountain top, nearly as deep as the Clear Ridge Cut that was located on the original 1940 Turnpike east of Everett. In clearing this cut, 5.5 million cubic yards of earth and rock were removed, five times the amount removed at Clear Ridge.

Laurel Hill Bypass indicated as under construction on the 1964 official state map. (Pennsylvania Department of Highways) |

Blasting at the Laurel Hill Bypass work site. (Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission) |

The second project to take place was the excavation of a second two-lane tunnel at the Allegheny Mountain Tunnel, which became the westernmost tunnel on the system with the closing of the Laurel Hill Tunnel. For a period, engineers wanted to utilize the never-completed South Pennsylvania railroad tunnel that lay adjacent to the tunnel. However, it was rejected this time for the same reasons it was rejected in 1939. The new tunnel cost $8.3 million and was carved out of the mountain 125 feet south of the original tunnel.

|

|

|

|

Many improvements over the original tube were made during the construction of the new tunnel. The most noticeable change was the brighter interior produced by the white-tile walls and fluorescent lighting. For the Turnpike maintenance crews, it was easier to maintain and clean than the old recessed lighting in the dingy concrete lining. The ventilation was improved with a more powerful system, increased clearances, and a completely new portal building and control center. The new tunnel opened to traffic on March 15, 1965, at which time the old one was closed for a $3 million revitalization project to bring it up to its twin's standards. The original tube reopened on August 25, 1966, and for the first time in the Turnpike's history, provided a trip through a tunnel not having to endure a merge at the tunnel's entrance.

While the opening of the new tunnel at Allegheny Mountain was taking the spotlight, studies were being conducted on what should be done with the remaining tunnels on the system. Parallel tunnels were shown to be the most economical solution to three other sites: Tuscarora Mountain, Kittatinny Mountain, and Blue Mountain. The first spade of dirt to be shoveled in the next round of tunnel construction occurred on April 11, 1966 just north of the original Tuscarora Mountain Tunnel when the $9.8 million project began. A week later, ground breaking took place for a $16.3 million project to bore tunnels south of the original Kittatinny Mountain and Blue Mountain Tunnels.

|

|

With the work on the Allegheny Mountain Tunnel completed, Laurel Hill Tunnel bypassed, and work underway to "twin" the Kittatinny, Blue, and Tuscarora Mountain Tunnels, attention focused on what to do with the remaining two mainline tunnels. An engineering report conducted by Buchart-Horn released in February 1961 produced five alternatives for congestion relief:

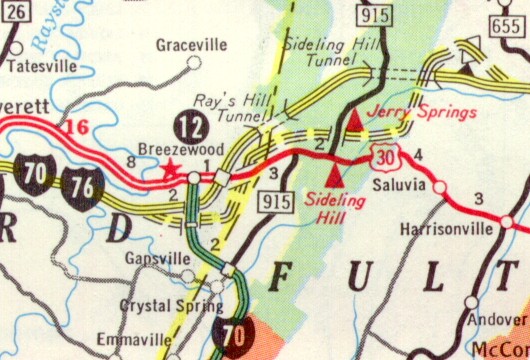

The Turnpike Commission concluded that the most efficient means of easing the congestion at the longest and shortest Turnpike tunnels, Sideling Hill (6,782 feet) and Rays Hill (2,532 feet) respectively, was to build a new 13.5 mile bypass. The commission awarded three contracts from July 1966 to March 1967 totaling $17.2 million for the roadway construction and another $2.5 million for a new Sideling Hill Service Plaza to replace the Cove Valley Service Plaza along the section of highway being replaced. The new plaza would be built with crossover ramps allowing it to serve both directions of travel.

Rays Hill-Sideling Hill bypass as indicated on the 1968 official state map. (Pennsylvania Department of Highways) |

|

|

The new Turnpike alignment passing over the Sideling Hill Tunnel. (Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission) |

As for design standards, the same used at Laurel Hill's bypass were also utilized in this project. Engineers kept the three percent grade, a wide median strip, and a third truck-climbing lane at each end of the new roadway. Going from west to east, the new alignment loops south of the existing highway, then crossed over to the north above Sideling Hill Tunnel which is six tenths of a mile longer than the 1940 alignment.

These projects, the new tunnels at Tuscarora, Kittatinny, and Blue Mountain and the Sideling Hill-Rays Hill bypass, opened to traffic on the same day: November 26, 1968. While the new tunnels were put into service, the original tunnels at those three sites were taken off-line to undergo a combined $11 million rehabilitation. Just as when the new Allegheny Mountain Tunnel opened, traffic was diverted through the new one while the old one was closed.

Resurfacing the Turnpike

in the 1950s, as the original

pavement began wearing

out. (PTC)

As the work on the tunnel situation was going on, the commission looked at the strain the interchanges were under, as many had not been enlarged since the highway opened in 1940. In October 1963, a $1.6 million construction project to replace the New Stanton Interchange began. The old interchange which required drivers to make left turns across traffic both within the layout and onto US 119 caused relentless traffic jams. On November 12, 1964, the new interchange opened with connections to I-70 and US 119, and became the first to be replaced, not just expanded.

The original layout of the New Stanton Interchange

after the Turnpike first opened. Quite

a drastic change from the current interchange. (Sidney Koch)

New Stanton was not the only interchange where capacity was increased. The Gateway Interchange had three more lanes added to bring its total to 11, the Pittsburgh Interchange's increased to 10 lanes, and a new Harrisburg East plaza was built to provide direct access to Interstate 283 and PA 283. All three projects cost more than $3.2 million and were completed in 1969.

The Harrisburg East Interchange as seen from the

PTC headquarters.

With the new Rays Hill-Sideling Hill bypass construction also involved a new Breezewood Interchange. The $3.1 million project increased the number of lanes from four to ten, to ease traffic using new Interstate 70. Part of the old highway became the new access highway to US 30 and the town.

Another interchange to be replaced was the Exit 286/Reading-Lancaster, which cost $2.7 million. The reason for the new configuration was that US 222 was being upgraded to an expressway on a new alignment east of the original interchange. Most of the busiest interchanges in the system were rebuilt, if not replaced, or enlarged with the addition of more lanes as traffic counts grew. A good example of this was the Perry Highway Interchange, now Cranberry, was enlarged because of the opening of Interstate 79.

New interchange layout for US 222. (Pennsylvania Turnpike

Commission)