I decided to set off on my literary journey of The Big Roads with an open mind and my Pennsylvania Turnpike bookmark. It seemed fitting considering I was reading a book about the Interstate System, and the Turnpike was one of the earliest segments of it that was completed.

When I say “an open mind” it is because I was a bit skeptical approaching reading this book. The reason being is there are many in the Pennsylvania Highways Library on the history of the Interstates. However, in the Introduction, author Earl Swift hooked me with his description of the trip across the country which he took to research The Big Roads. As part of that trip, he came through the southern portion of the Commonwealth on the historic Lincoln Highway. Earl, his daughter, and a friend of hers stayed on the Lincoln through Buckstown to Ligonier and eventually onto Pittsburgh, “…crawling from one stoplight to the next…” Unfortunately, that is a realistic description of travel down US 30 through Westmoreland and Allegheny counties!

The book takes readers on a journey, with a focus on persons who made the transition happen. Starting with Carl Fisher, a businessman in Indianapolis, who began his career selling bicycles. He then moved onto the “horseless carriage.” To demonstrate the power of the car, he built a racetrack outside Indianapolis. Once it was repaved with brick, the power of the automobile could be exhibited in the way he intended. He also got into the road-building business by backing the creation of the Lincoln Highway and its north-south counterpart, the Dixie Highway.

Along the way, author Swift introduces us to Thomas Harris MacDonald. Mr. MacDonald started his career in roads in Iowa by laying out their system. Then the Feds tapped him to do the same on a national scale. We also meet Dwight D. Eisenhower, who in 1919 as a young Army officer, got a yearning for good roads after a cross-country trip on the Lincoln Highway. Just under three decades later, he would experience superb roads — just not on this continent.

The one good road, whose idea and planning came from those Ike saw in Germany which were the forerunner of the Interstate System, was our very own Pennsylvania Turnpike. Just as safety was an impetus for the construction of the Interstates, the Turnpike was constructed to provide a safer alternative than the windy, mountainous, and narrow US 30. That was the primary route between Pittsburgh and the Mid-State area at the time.

Once Eisenhower got into the White House, he pushed for the need for high-speed, limited-access highways. He had seen the Autobahn used by his military to speed across Germany en route to Berlin. He did not need to look far for ideas. The Bureau of Public Roads had drawn up plans for such expressways; albeit tolled, while Ike was the Supreme Commander in World War II.

“The more things change, the more they stay the same” is a saying that often rings true. When talking about the debate Congress had over the Federal Aid Highway Act, it rings like Big Ben at high noon. Some legislators came out in favor of the plan. Others like Senator Albert Gore, the inventor of the Internet’s father, argued that it “…could lead the country to inflationary ruin.” Senator Harry Byrd said that “…nothing has been proposed during my twenty-two years in the United States Senate that would do more to wreck our fiscal budget system.” I’d hate to see what the “talking heads” on CNN, MSNBC, and Fox News would have said had those channels existed at the time.

The Big Roads is not just a reflection on how the highway system of the country changed, but how the country itself changed. The Interstates allowed the movement of goods and people in a short amount of time. They did so safely without the worry of cross-streets, traffic signals, stop signs, or rail crossings. These limited-access roadways all but eliminated head-on accidents in a uniform, monotonous drive devoid of local flavor. They also allowed for the growth of cities by pushing the suburbs farther out. This helped in the creation of satellite cities along beltways and bypasses. However, their paths into and through the cities would be a double-edged sword.

As I said in the beginning, I have other books on the Interstates and wondered how this book would differ. My answer would come in the final chapters of the book. The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 came into being just before the tumultuous 1960s. It was this period when the struggle for civil rights would reach its pinnacle. Urban Interstate routes were once seen as a way to rejuvenate the nation’s cities. At the same time, they were clearing out undesirable sections. The problem was that those undesirable sections contained people. They did not want to lose their homes just so suburbanites could get downtown quicker.

One such person was a man by the name of Joe Wiles. Mr. Wiles lived in the Rosemont section of Baltimore, which was under attack by Interstate 70. Mr. Wiles led a revolt against construction of I-70, which was both successful and unsuccessful. His revolt had been initially successful when its planned route through the City of Baltimore cancelled. However, it was also unsuccessful because discussions of the impending expressway doomed Rosemont to neglect. Ironically, it had become the type of area that would be favorable as an Interstate corridor.

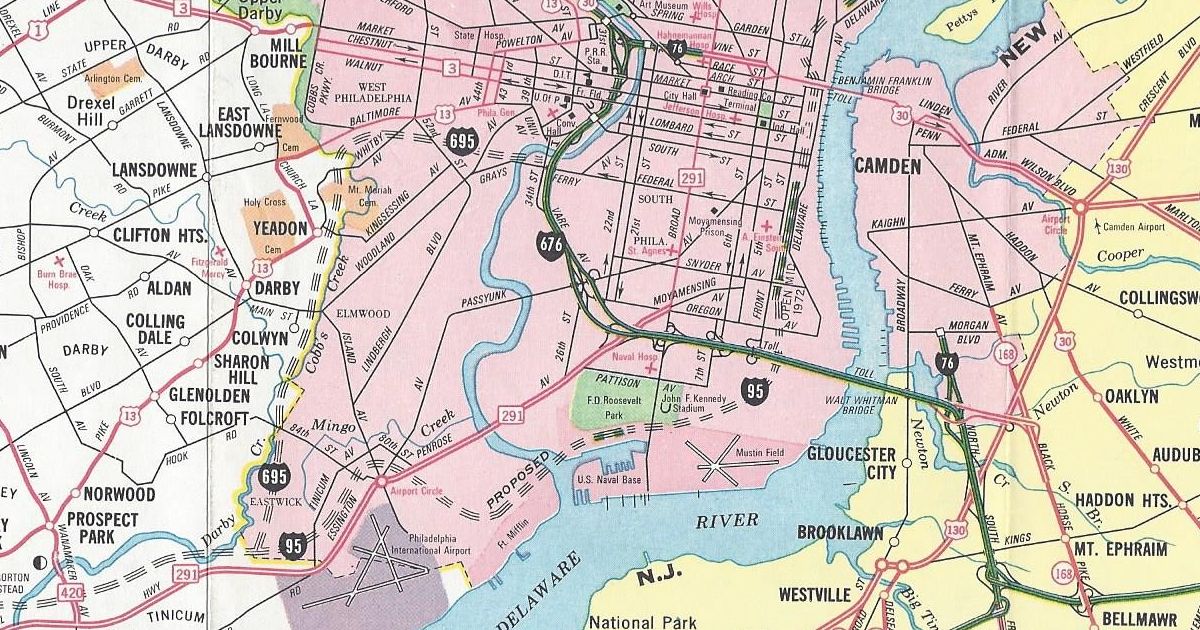

Black neighborhoods seemed to be under attack across the country. From Nashville where Interstate 40 was planned to isolate about 100 blocks from the City, to here in Pennsylvania where Interstate 695 in Philadelphia, known as the Crosstown Expressway, was to sequester black neighborhoods from Center City. These seemed like classic examples of white men’s roads going through black men’s homes.

Those other books in the Library only talk about the positive aspects of the Interstates. They hardly discuss the turmoil they caused as they carved their way across the country. I admire that Mr. Swift mentioned the issues of the urban routes through Baltimore, for example. When I write about the history of a route, I, too, mention the negatives in addition to the positives. I am glad to see a publication which does the same.

In conclusion, I would recommend The Big Roads. It is a well-rounded look at how we have progressed from roads that were narrow, dirt paths to today’s wide, concrete expressways. It makes for a good read, especially stuck in traffic on one of the Interstates.

If you would like to purchase a copy, drive over to the Pennsylvania Highways Bookstore.